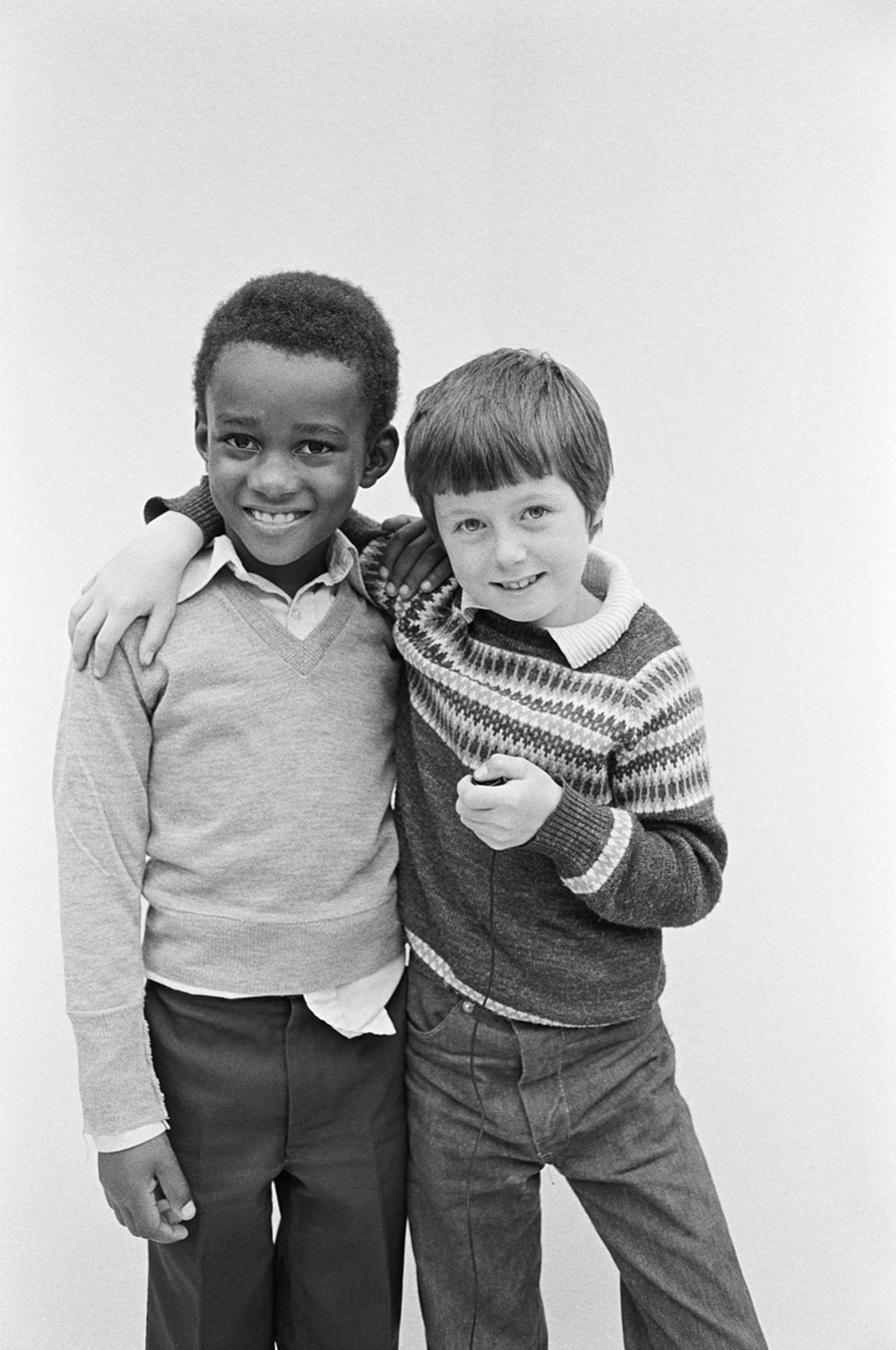

The subtitle of Patrick Waterhouse’s latest work, Restricted Images, is Made with the Warlpiri of Central Australia – and the word ‘with’ is notable. Over repeated trips, the 37-year-old Briton began to collaborate with, photograph and collect the work of Warlpiri artists, basing himself at the Warlukurlangu Artists art centre in the Northern Territory, five hours’ drive from Alice Springs.

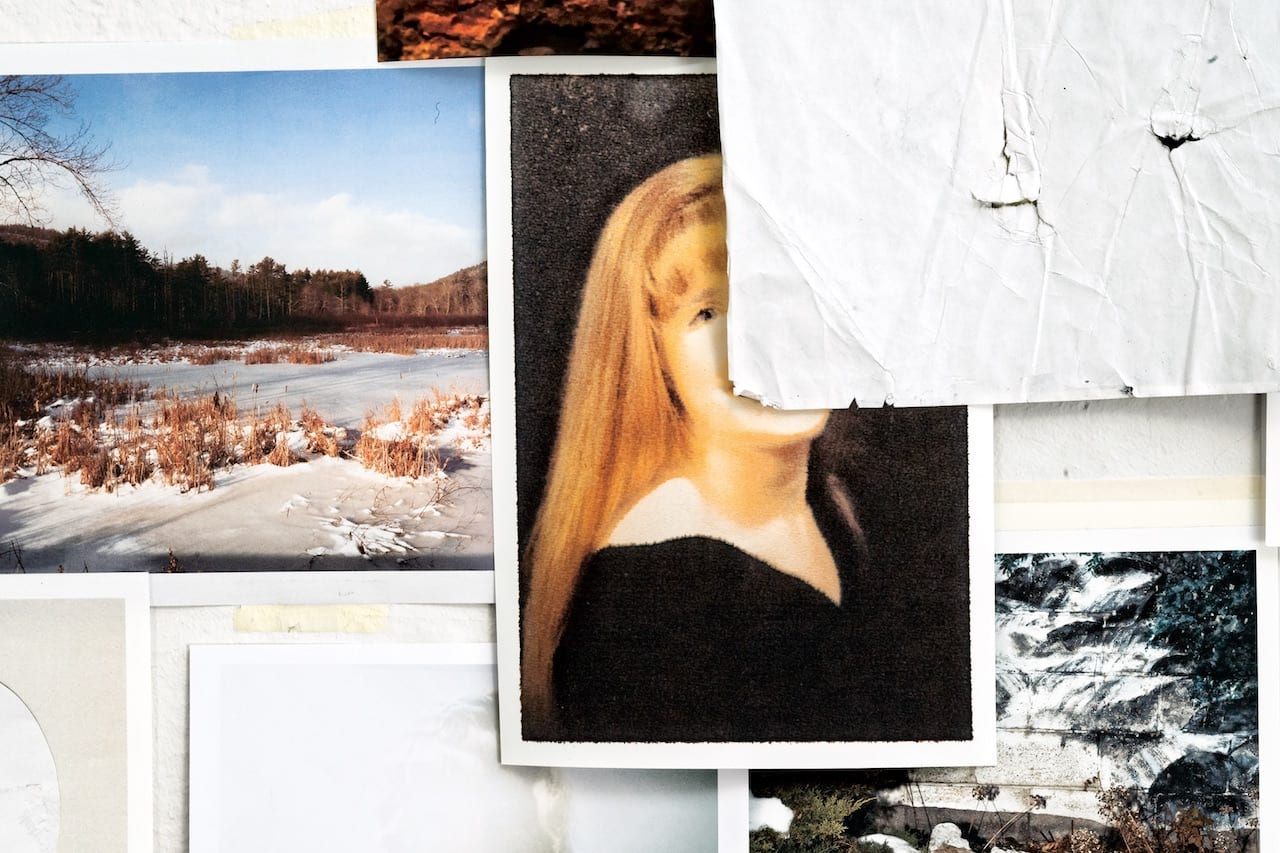

“I wanted to create a situation where the people I was working with had an encounter again, a chance to flip the power dynamic,” he tells me over coffee at his new studio in east London. He is surrounded by prints from the series, neatly packaged and ready to travel with him two days later to Australia for the next chapter of a project that started in 2011 when, through his editorship of the iconic Colors magazine, he first visited the art centre. “I wanted to give the people in this community agency over their own representations,” he says.