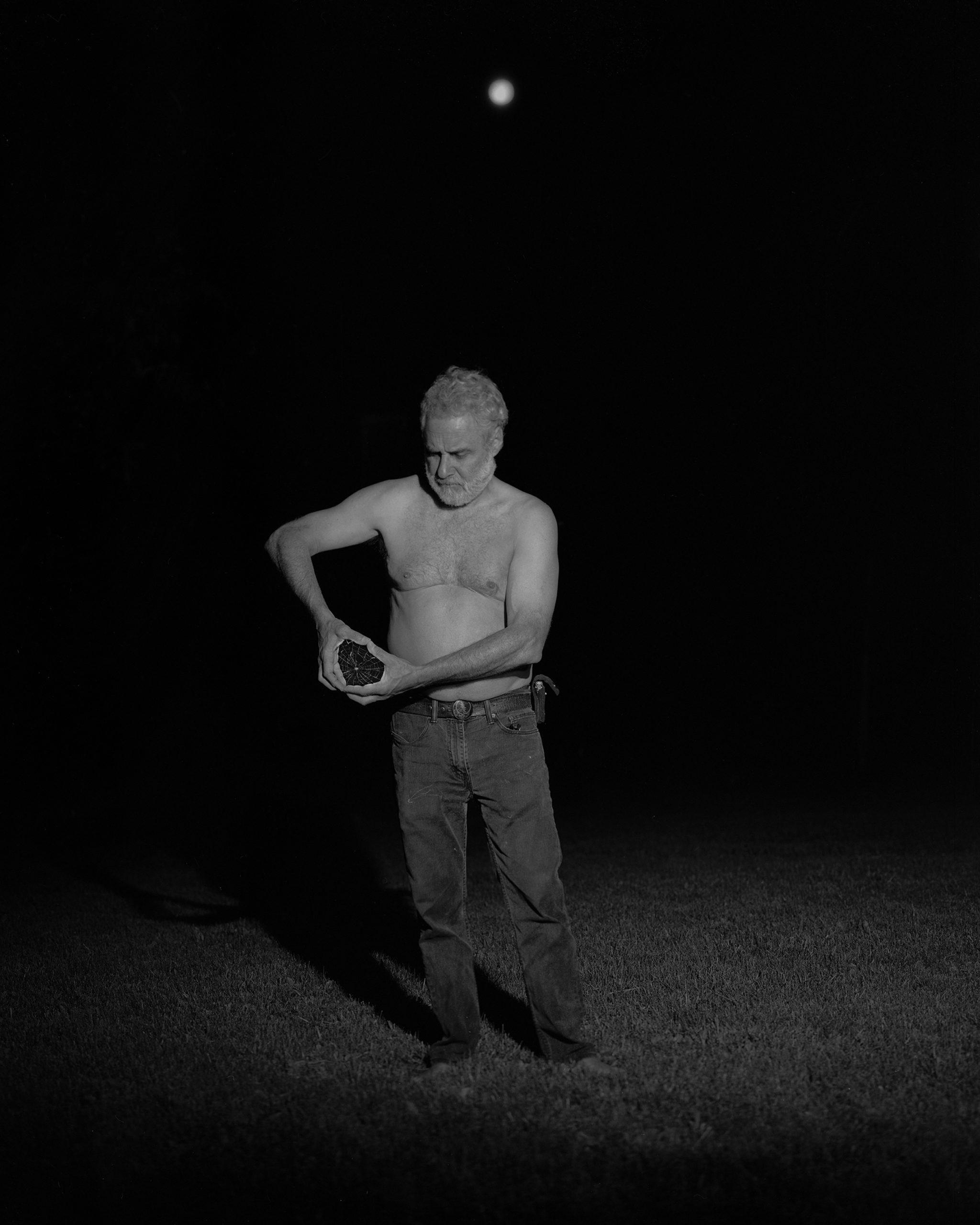

Known for their eerie, black-and-white flash photography, Hausthor unpacks how their half-broken camera and decade-old flash produce haphazard images that prioritise the moment

Words by Dylan Hausthor, as told to Cat Lachowskyj.

My interest in flash started at the age of 16, when I realised I wanted to make pictures at night. At first I used a headlamp, but I didn’t have a tripod, so everything I made was blurry. Eventually, I found a shitty flash on eBay by googling “brightest flash”; that ended up being my light for ten years. It took me a while to understand that I had to sync the device with the camera, so for a good four months I was making photographs that were half-exposed. It was a Vivitar 283, and it finally broke a few weeks ago. I just upgraded it for the first time in my life.

As you can probably tell, I’m not technically advanced when it comes to photography. I know so little about gear, and my style has evolved directly out of never fully understanding my camera. In addition to my early flash experiments, I would shoot everything with my aperture wide open, which is what slowly led to the look of the photos in my project Sleep Creek with Paul Guilmoth. Working this way meant that anything within five feet of me would be totally overexposed. I also don’t own a light meter, so I guess all of my exposures, night and day.

I used a half-frame camera for years because I couldn’t afford regular film (half-frames allow for one roll to yield 72 images). I still have old binders full of thousands of pictures on obscenely small negatives: all flashed and blown out because I didn’t understand what I was doing. Eventually, Paul and I each bought a Graflex from a guy selling them for $100 in northern Maine, and he also gave us a trash bag full of expired film, which was incredible. We shot that to death. Then, recently, I got a new Graflex for $50 at a garage sale.

I have two lenses: one’s shutter doesn’t work, so I use it as a nighttime lens; on the other one, an aperture blade is stuck open. I kind of cover the lens, open it to take the image, and then close my hand over it again. My new flash is a giant Godox studio one that runs on a battery. Because it has no cord, I can do much weirder stuff with it, which is exciting.

There are times when I have had to conceptually defend using flash, and my answer has always been the same. I’m interested in making images that look how they feel — not necessarily like how we see things with the naked eye.

Making photographs with flash manifests scenes that, rather than reflecting how people look at things, serve as proof of the camera’s existence. I glaze over when I see photographs that act like a rendering [of something], but I love it when photographs are self-referential of their own making. Flash is such a fool-proof way to communicate that sentiment.