This article is adapted from a series of features originally published in issue #7889 of British Journal of Photography magazine. Visit the BJP Shop to purchase the magazine here.

British Journal of Photography is dedicated to seeking out new talent. Each year, the print magazine platforms 12 exceptional emerging photographers graduating from colleges and universities across the UK.

After sharing the first and second round of graduates over the last two months, below, BJP-online presents the final instalment of UK graduates featured in our November issue.

—

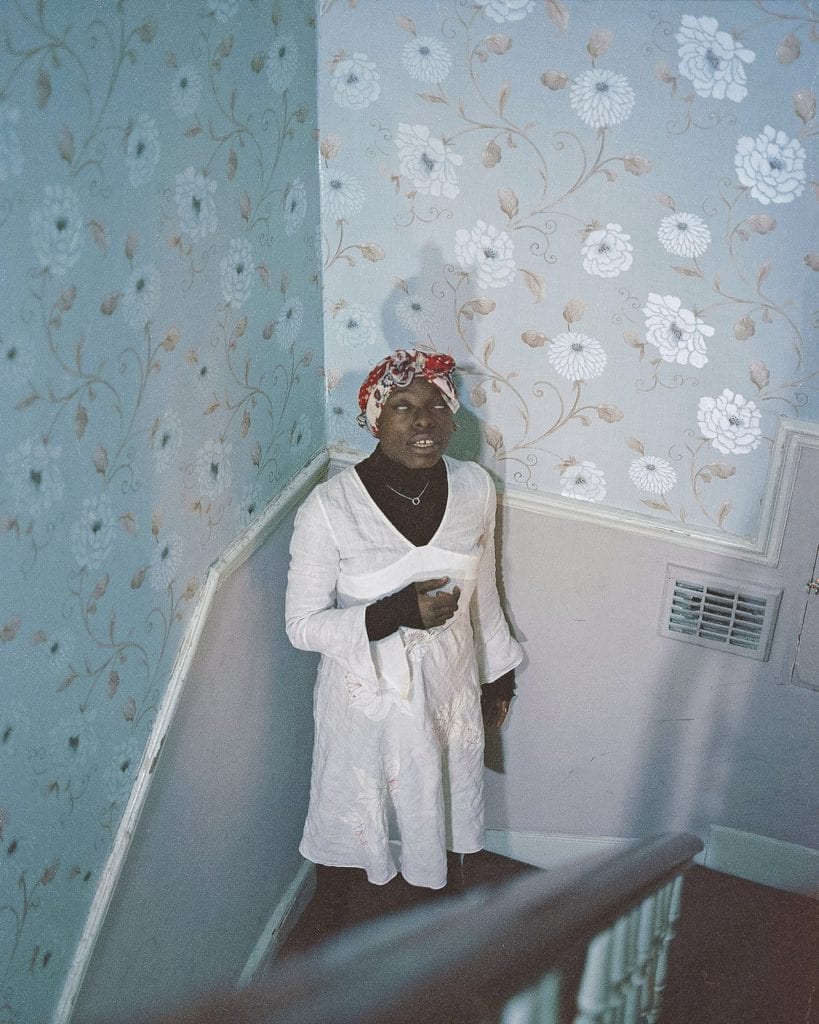

Hannah Sommer

University of Westminster

London’s Portobello Road is both inspiration and backdrop for American-born artist Hannah Sommer’s project, The bottom of the hill. After visiting the area in west London for the first time when she was 13, and being “immediately enthralled by its charm”, she knew it was the place she wanted to live when relocating to the UK to study photography.

Upon her arrival, Sommer, now 22, began picking up jobs at Portobello Market, including selling doughnuts, vintage clothes and vinyl records, and it wasn’t long before she developed friendships with many of the area’s long-standing residents.

“Listening to their stories, I discovered the multitude of layers within the community, and its rich history in arts, subculture and civil rights,” she says. “Then the devastation of the Grenfell fire in 2017 gave me another perspective on the area, and a sense of faith, because I had never seen such strength and love between people after so much loss.” It was the way the community pulled together, despite ostensibly being forced apart, that inspired her to create a project celebrating the people who have long called this place home.

When it comes to making documentary work, Sommer likes to take her time to get to know the people she photographs. “The subjects I have chosen have unique ties to the community that have made them integral figures of the local social landscape.”

Sommer is now working towards a second edition of the project, which will include personal accounts, original artwork and writings by her subjects, in order to “broaden the narrative of this special place”.

—

Olimpia Piccolo

University of the West of England

Since moving to the UK from Rome three years ago, Olimpia Piccolo can look at her life back in Italy with fresh eyes. “I’ve been thinking a lot about the rich history of the city I grew up in, and it’s made me observe my culture and family there in different ways,” she says. “Where once I was sceptical, now I look at it with rose-tinted vision, and I’ve become a lot closer to my mother since moving too.”

The changing dynamic of their relationship, as each of them adjusted to living apart, is what inspired Piccolo’s final university project, All Good and Very Happy?, which playfully stages portraits of her mother, self-portraits and still lifes shot with a heavy flash. “When it came to my final-year project, I wanted to take the opportunity to get to know my mother more through the lens,” Piccolo explains. “My aim was to narrate both sides of our relationship through images that were tinged with nostalgia, but I also wanted it to be light-hearted and a little humorous.” The title of the project is a nod towards their correspondence with one another.

For Piccolo, having dual nationality as an Italian-American meant that she absorbed different aspects of both cultures when developing her photographic eye, and as a result her pictures present an eclectic mix

of props and objects, from Roman statues, columns and busts, to soccer socks and stuffed Disney characters. “I wanted to feature all of the cultural elements and symbols that formed me, and put my own spin on them,” she explains. “I like documentary subjects and natural compositions, but I’ve also always loved surrealist photography, styling, and staging scenes before the camera.”

That love of surrealism extends to the way she photographs, with bodies often seen in fragments; legs poking out from behind curtains, a head wrapped in fabric, or arms appearing detached from a torso. “I want my images to tell partial truths, like parts of the story, and for the viewer to guess at the rest.

—

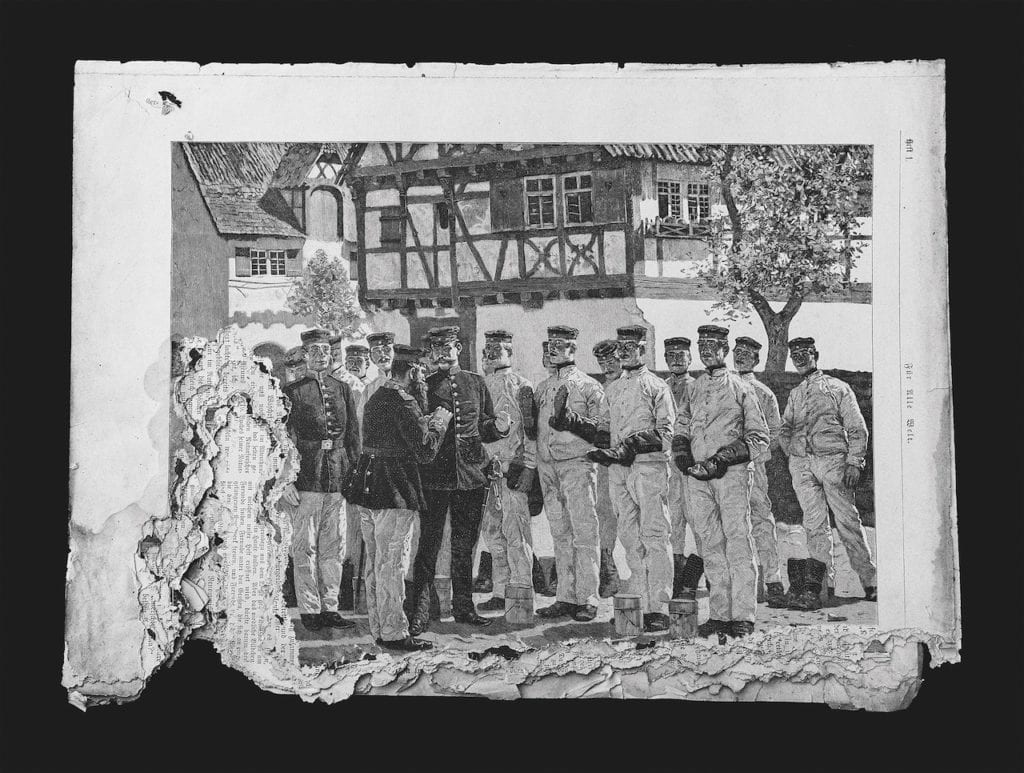

Elena Helfrecht

Royal College of Art

After her grandmother passed away, Elena Helfrecht and her mother began the difficult task of going through their late relative’s belongings in their home in Bavaria, which has been in the family for 200 years. Delving deep into the family’s past, they began to uncover stories that intrigued them, and for Helfrecht, this sparked her ongoing project, Plexus.“I found many documents and artefacts that had lost their histories, of which I could recover some by adding my own narrative,” says Helfrecht.

The work centres around one key incident involving the death of her great-grandfather during the Second World War. “After the disappearance of my great-grandfather, my grandmother – back then just a child – was adopted by her grandmother and grew up on the other side of Germany in a harsh postwar environment without her parents,” recounts Helfrecht. “This event tore a hole in her life that was never closed and grew larger until it reached my mother and I. Only now are we slowly able to repair it together through dialogue, research and art.”

Rendered in black-and-white, the objects and spaces in Helfrecht’s images take on a dream-like and sometimes sinister feel, and the work seems to be suspended between a troubled past that weighs heavy on the present and an uncertain future. Themes such as war, memory, inherited trauma, personal and collective histories, and mental health permeate the work, which Helfrecht began in 2018 while she was studying in London. Although she has been working on it for some time, there is still more to do.

“I want to allow the work to develop in a natural way and with the current events of my time depending on what I see and discover,” she adds. “It feels like I will need a lot of images in order to tell the whole story.”

—

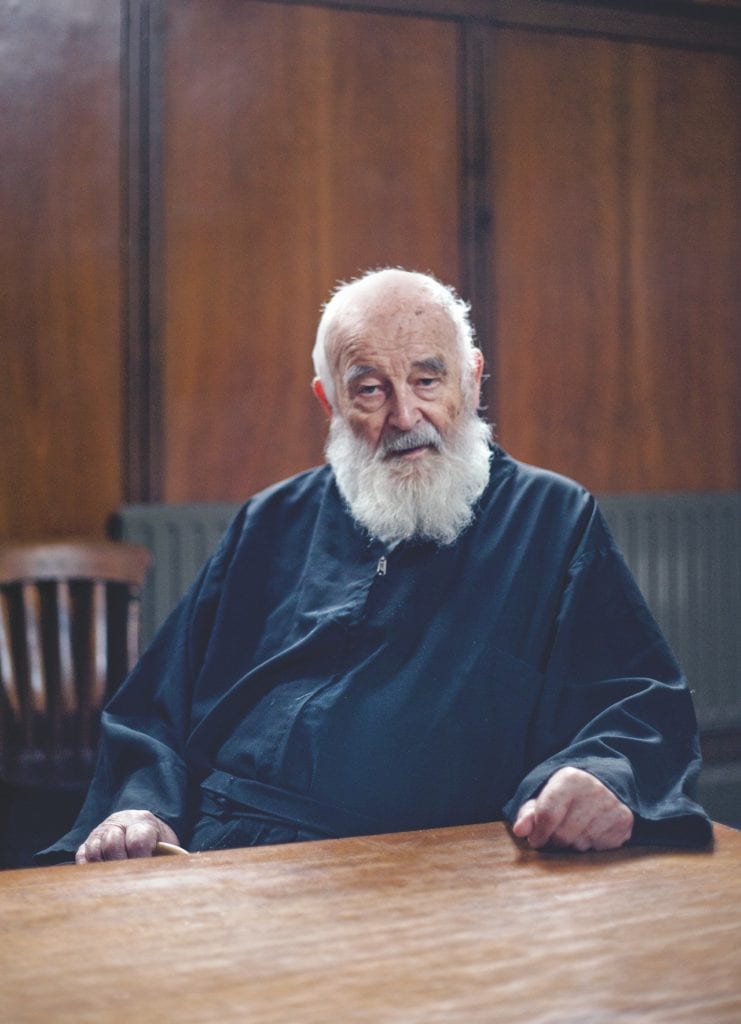

John Boaz

Birmingham City University

In Our Father, John Boaz delves into Britain’s monastic communities with a considered combination of photographic portraiture, still-life images and quietly observed landscapes and interiors. His subjects – Christian monks and nuns of both Roman Catholic and Anglican orders who have devoted themselves to God – are pictured going about their daily lives as they practise their faith unconditionally.

“I wanted to understand more about these communities – how they express and live out their faith and spirituality,” the 23-year-old says. “The fact that these communities still exist fascinates me.”

Boaz contacted several Christian monastic communities in the UK, and the responses were mixed. Some declined “for good reasons” (he doesn’t elaborate), but four communities in England and Scotland agreed to be photographed. “What helped me was the fact I was clearly interested in their communities, and I made sure this came across,” says Boaz. “I think it also helped that I talked about my own upbringing in a modern evangelical Christian community, and how I had given my life to God in recent years.”

A sensitive approach was paramount when making the work, as well as the importance to take what he calls “a visually poetic and creative approach to documentary”, which involved including still-life images alongside portraits, and incorporating light and texture. “I wanted to try and capture the sense of spirituality, mystery and beauty of these communities,” he says. “I have always had a love for the complexity, diversity and beauty within humanity.”