Michalis Poulas has lived in Crete for much of his life. It was here that he first learned the technicalities of photography from his father, who opened a film-processing shop on the Greek island in 1988, and here that he built a career as a professional photographer. Shooting mostly on digital, in 2014 he decided to revisit the world of medium format, and with all the languidness that such work entails, it seemed natural that the island should serve as his subject.

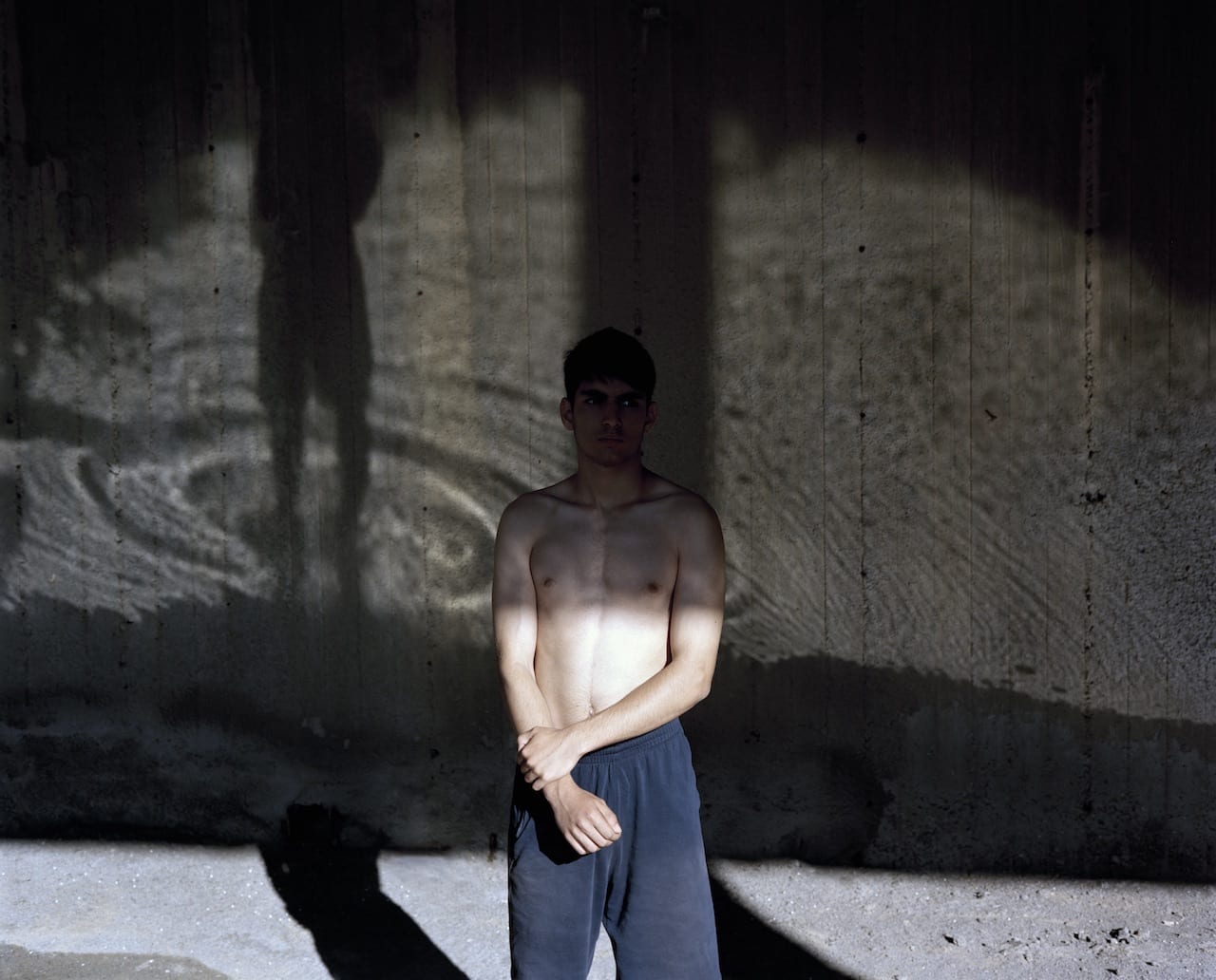

The result is Infinite Perimeter, an as- yet-unfinished series which looks at a decade of sociopolitical unrest on the island with a cool objectivity. While all the images were taken in Crete – 90 per cent of them within 10 kilometres of Poulas’s home – this is neither documentary photography, nor a series about Greece specifically. Rather, it’s about the instability permeating the Western world today.

“For what I need to do, I don’t need to go far,” Poulas explains. “I need the place to be no place. It’s not Crete – it’s the feeling and the atmosphere that I want to communicate.”

In photographs of empty, windswept landscapes and abandoned structures, floating quietly to the surface are the undertones of economic pressure, fatigue, poverty and unease. This is a work about human identity, left fragmented by the deterioration of capitalism, Poulas explains – and it’s embodied poignantly in these calm snapshots of his local area.

If Crete is both protagonist and silent bystander in his work, the series’ other main character is the Swedish mathematician Niels Fabian Helge von Koch. He discovered the eponymous Koch snowflake, one of the first examples of a fractal – a curve of infinite length outside a bounded area. This pretty form appears to be simple, but in fact it fractures to produce an endless void. The futility which underpins this complex concept resonated with Poulas, who recognised in it the key tenets of our modern condition, and drew on the accompanying text for the series title.

“Imagine you have a shape and the perimeter is growing and growing infinitely, but the space inside it stays the same,” Poulas explains. “It’s like a fence that’s keeping people outside of an imaginary shape” – one that’s constantly growing, but also stays the same size.

This idea is thrown into stark relief by the refugee crisis so familiar to residents of the Greek islands, Koch’s snowflake seeming in that context to reflect the European border. Poulas’s hope in making this series has always been for a kind of catharsis, he says, though he believes this to be wishful thinking.

michalispoulas.com This article was first published in the December issue of BJP www.thebjpshop.com