Rob Hornstra moved to Ondiep in Utrecht in 2004, soon after his graduation from the Dutch city’s art academy. This is an archetypal working-class neighbourhood, where stark architecture and troubled residents contrast with the picturesque city centre, with its canals and gabled houses. Ondiep is both close to and far from that hub of bustling bars and restaurants. Why on earth did Hornstra opt to live here?

“It’s not easy to find proper housing in Utrecht,” the documentary photographer says. “So I was forced to apply for social housing. But I also made the conscious decision to locate myself in this ‘down-to- earth’ environment because I’m fascinated by the straightforwardness of the people who live here. You’ll never be one of them, but it’s not impossible to become adopted and thus arrive at a better understanding of their perspective on the world. I, at least, managed to do so.

“Directness means clarity and I like that. I lived there for almost a decade and, throughout that period, the possibility of the building being knocked down was always there. Although the housing agency remains undecided about the status of this apartment, after I moved out in 2011 I was offered the chance to keep it as a studio. Now this place more or less serves as my workspace, as storage for the books I have self-published and also as a kind of residency, as I welcome colleagues from all over the world to stay and work here.”

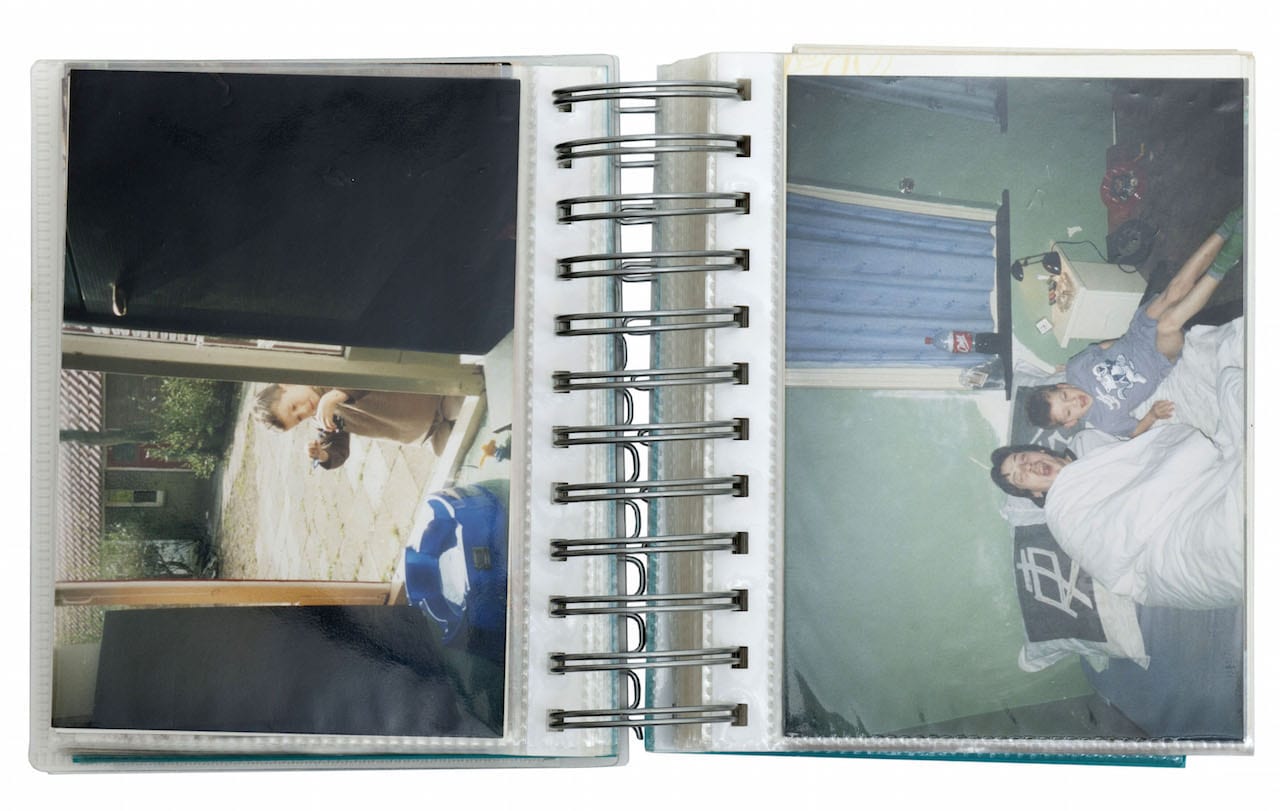

Utrecht, Netherlands, 2008. Kid calls his mother from his bedroom in the Utrecht district of Ondiep. Because he never has credit on his own phone, he is dependent on his neighbours’ phones. He often gets up as soon as he has woken up and, wrapped in a blanket, goes to their door to ask if he can make a call. From the series Man Next Door © Rob Hornstra

“We’ll probably not pull off another mega-story in the same scheduled way,” says Hornstra. “We both arrived at a new stage in our lives that forces us to improvise and we accept it. There’s still the intention to work together in the near future but after The Sochi Project I’ve been focused on finding a way to share my long term commitment to Ondiep with an audience.”

He eventually moved elsewhere in the city but others remained in Ondiep as their families grew, despite many housing association properties being scheduled for demolition or renovation. “The strategy is to replace these houses with more expensive apartments [for sale and rent]. This means the natives have to move out and live elsewhere; my next-door neighbour was one of them,” says Hornstra, referring to the subject of his latest book and exhibition, Man Next Door.

“Kid was a bit of a boorish figure – a troubled man with limited capacities. He could also show his bad temper sometimes, so I can understand why many people found his bellowing voice and coarse speech intimidating. Over the years, I saw the police delivering him home several times after short detentions for various minor misdemeanours he apparently committed. Kid was also addicted to hard drugs, but I only understood all this at a later stage.

“He was a different person when he allowed me into his apartment, where I got to see another side of his character. The pride in having snakes for pets, for example. He loved to make a show of feeding them a rat. There was also the sadness of being banned from seeing his son. Kid had trouble understanding life and how to function in society, that much was clear to me. He could hardly read or write and was at the edge of being able to live independently. In that sense, I’m proud of our so-called welfare state – of how everything is done not to give up on figures like Kid.”

From the series Man Next Door © Rob Hornstra

His former home is built on what was once the shallow area of a river (Ondiep literally means ‘not deep’), but this ‘shallowness’ also relates to how the people who live here are looked down on by others. “I can become really enraged by such highbrow snobbishness,” says Hornstra.

“I’m really pleased I could invite people from Kid’s social realm to the opening of the project in the Centraal Museum – a space that they would be unlikely to visit otherwise – and to have them mingle with the typical art crowd that attends such events. Regardless of who shows up, I also started a crowdfunding campaign to establish a 60-copy special edition of the book that I will offer to family and friends of Kid.”

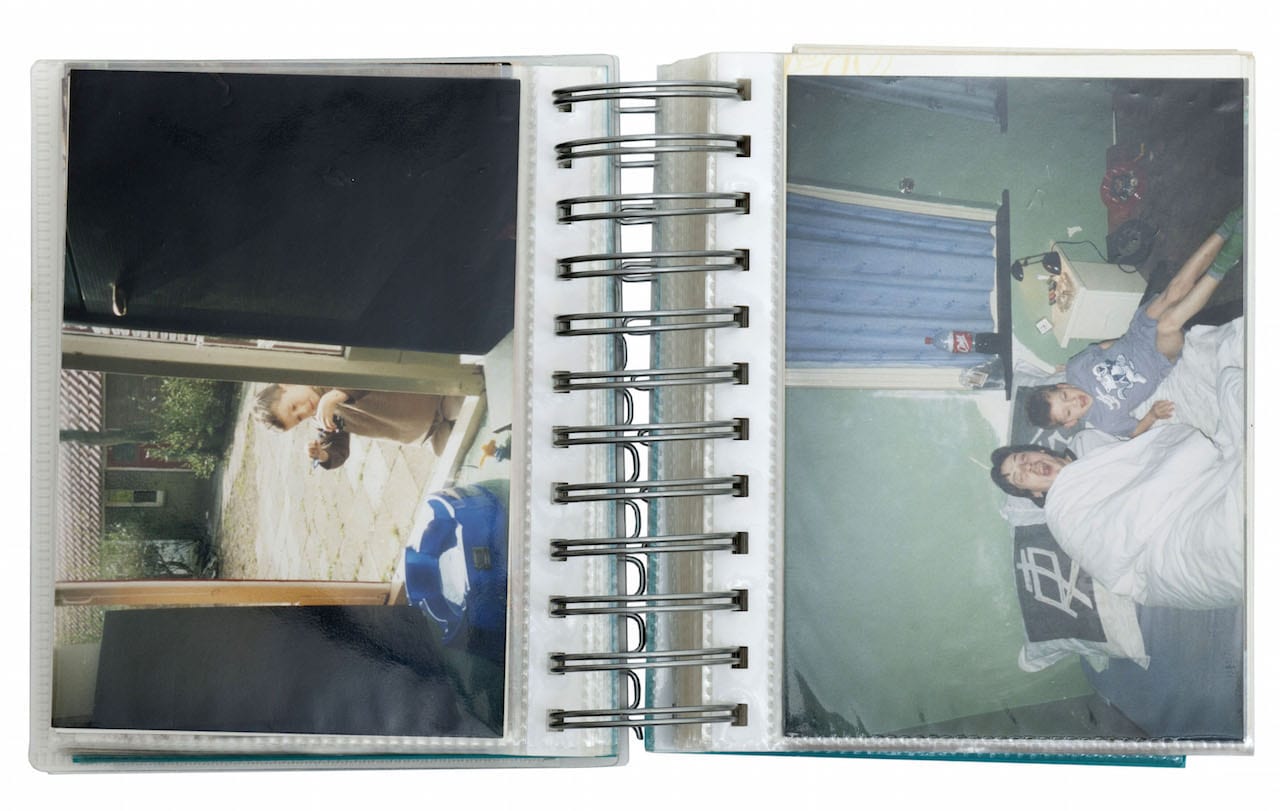

Utrecht, Netherlands, 2010. Portrait of my neighbours Willem & Kid in the Utrecht working-class neighbourhood Ondiep. I will continue to follow them until we are all forced to leave as a result of housing development plans. From the series Man Next Door © Rob Hornstra

Hornstra doesn’t consider himself an activist, however, but an artist, driven by curiosity. “Let’s be clear: this is an art project, not some kind of social avocation. Furthermore, Man Next Door is not a reportage about Ondiep. Kid is the protagonist here and in the book I also exclusively focus on him as my next-door neighbour. In fact, until his tragic death in 2013 – Kid was found drowned in a canal in Utrecht – I knew very little about his shady activities outside his home. In the last year of his life I lost touch with him, while he spent more and more time with drifters and junkies, begging on the street for change.”

Utrecht, Netherlands, 2010. A portrait of Kid. From the series Man Next Door © Rob Hornstra

“This is certainly the case for police reports that I collected. In the museum I’ll present them as complete documents, whereas in the book I use quotes from them. Their value lies in showing aspects of Kid’s life that I could never capture with my camera because he only allowed me into his world at certain moments, when he was home and in a good mood. In the book, the relaxed guy you see in the portraits is juxtaposed with his shadow side, with the darker aspects of his life. In that way I hope to give an honest and more complete picture of Kid.

“I have a similar archive of my other next-door neighbour, Willem, who was also a typical resident of this area, albeit of a completely different character. Who knows? Perhaps I will publish Willem’s portraits as a next chapter of my long-term commitment to Ondiep. Time will tell.

“But first things first: after the opening of the exhibition at the Centraal Museum, I will partner with Robin de Puy – who I actually consider much more talented when it comes to ‘pure’ portrait photography – and together we’ll invite all 60 of Kid’s friends and family members to this place, his former next-door apartment that now serves as my studio. So even though the project has finally landed – as a book and as an exhibition – it is clearly far from absolute completion.”

Man Next Door is on show at the Centraal Museum, Utrecht from 02 December until 25 March. centraalmuseum.nl robhornstra.com

Utrecht, Netherlands, 2008. Kid has just been brought home by the police after being found with bare feet and in a confused condition in the Schaakbuurt, about 1.5km from his house in the Utrecht district of Ondiep. He has huge blisters on the soles of his feet. Especially at tense times, Kid often suffers from severe epileptic attacks and moments of narrowed consciousness. He cannot remember anything from his Sunday morning walk. From the series Man Next Door © Rob Hornstra

“It’s not easy to find proper housing in Utrecht,” the documentary photographer says. “So I was forced to apply for social housing. But I also made the conscious decision to locate myself in this ‘down-to- earth’ environment because I’m fascinated by the straightforwardness of the people who live here. You’ll never be one of them, but it’s not impossible to become adopted and thus arrive at a better understanding of their perspective on the world. I, at least, managed to do so.

“Directness means clarity and I like that. I lived there for almost a decade and, throughout that period, the possibility of the building being knocked down was always there. Although the housing agency remains undecided about the status of this apartment, after I moved out in 2011 I was offered the chance to keep it as a studio. Now this place more or less serves as my workspace, as storage for the books I have self-published and also as a kind of residency, as I welcome colleagues from all over the world to stay and work here.”

“We’ll probably not pull off another mega-story in the same scheduled way,” says Hornstra. “We both arrived at a new stage in our lives that forces us to improvise and we accept it. There’s still the intention to work together in the near future but after The Sochi Project I’ve been focused on finding a way to share my long term commitment to Ondiep with an audience.”

He eventually moved elsewhere in the city but others remained in Ondiep as their families grew, despite many housing association properties being scheduled for demolition or renovation. “The strategy is to replace these houses with more expensive apartments [for sale and rent]. This means the natives have to move out and live elsewhere; my next-door neighbour was one of them,” says Hornstra, referring to the subject of his latest book and exhibition, Man Next Door.

“Kid was a bit of a boorish figure – a troubled man with limited capacities. He could also show his bad temper sometimes, so I can understand why many people found his bellowing voice and coarse speech intimidating. Over the years, I saw the police delivering him home several times after short detentions for various minor misdemeanours he apparently committed. Kid was also addicted to hard drugs, but I only understood all this at a later stage.

“He was a different person when he allowed me into his apartment, where I got to see another side of his character. The pride in having snakes for pets, for example. He loved to make a show of feeding them a rat. There was also the sadness of being banned from seeing his son. Kid had trouble understanding life and how to function in society, that much was clear to me. He could hardly read or write and was at the edge of being able to live independently. In that sense, I’m proud of our so-called welfare state – of how everything is done not to give up on figures like Kid.”

His former home is built on what was once the shallow area of a river (Ondiep literally means ‘not deep’), but this ‘shallowness’ also relates to how the people who live here are looked down on by others. “I can become really enraged by such highbrow snobbishness,” says Hornstra.

“I’m really pleased I could invite people from Kid’s social realm to the opening of the project in the Centraal Museum – a space that they would be unlikely to visit otherwise – and to have them mingle with the typical art crowd that attends such events. Regardless of who shows up, I also started a crowdfunding campaign to establish a 60-copy special edition of the book that I will offer to family and friends of Kid.”

Hornstra doesn’t consider himself an activist, however, but an artist, driven by curiosity. “Let’s be clear: this is an art project, not some kind of social avocation. Furthermore, Man Next Door is not a reportage about Ondiep. Kid is the protagonist here and in the book I also exclusively focus on him as my next-door neighbour. In fact, until his tragic death in 2013 – Kid was found drowned in a canal in Utrecht – I knew very little about his shady activities outside his home. In the last year of his life I lost touch with him, while he spent more and more time with drifters and junkies, begging on the street for change.”

“This is certainly the case for police reports that I collected. In the museum I’ll present them as complete documents, whereas in the book I use quotes from them. Their value lies in showing aspects of Kid’s life that I could never capture with my camera because he only allowed me into his world at certain moments, when he was home and in a good mood. In the book, the relaxed guy you see in the portraits is juxtaposed with his shadow side, with the darker aspects of his life. In that way I hope to give an honest and more complete picture of Kid.

“I have a similar archive of my other next-door neighbour, Willem, who was also a typical resident of this area, albeit of a completely different character. Who knows? Perhaps I will publish Willem’s portraits as a next chapter of my long-term commitment to Ondiep. Time will tell.

“But first things first: after the opening of the exhibition at the Centraal Museum, I will partner with Robin de Puy – who I actually consider much more talented when it comes to ‘pure’ portrait photography – and together we’ll invite all 60 of Kid’s friends and family members to this place, his former next-door apartment that now serves as my studio. So even though the project has finally landed – as a book and as an exhibition – it is clearly far from absolute completion.”

Man Next Door is on show at the Centraal Museum, Utrecht from 02 December until 25 March. centraalmuseum.nl robhornstra.com