It sits next to an off-licence called Mr Booze, opposite a takeaway burger joint, a newsagent and a pub. In the windows are the type of portrait you see in high-street photography studios in cities and towns anywhere in the UK. But look closely and there’s something different about WW Winter Photography Studio.

Here, just a stone’s throw from Derby train station, is the world’s oldest photography studio, an establishment that has photographed generations of the city’s inhabitants since 1867. From when Walter William Winter opened his first dedicated photographic studio, it has been passed down “like a torch” from apprentice to apprentice, taking portraits for more than 15 decades.

In 2013, Debbie Adele Cooper created a self-initiated artist residency at the studio. While exploring the building, she discovered a bricked-up partition in a dingy, damp corner of the junk-strewn basement. Knocking through the brickwork she unearthed something thought to have been lost for all time: a slew of glass-plate negatives dating back to the mid-19th century.

“There’s probably 10 years’ worth of archiving work here,” Cooper says, as she shines the light of her iPhone onto the archive, where it still sits in the studio’s basement. Not all the archive survived. Half of the building was sold off in the mid-20th century and subsequently demolished, and so too were several tonnes of glass – thousands of negatives destroyed in a few days.

It’s perhaps unique in the UK; a privately-owned archive that stretches back to the early days of the medium, charting its relationship to society through all its evolutionary stages, right up to the present moment. Yet Winter’s glass plates lay forgotten, uncared for and victim to the elements for decades.

The archive has already been shown to the people of Derby, in a project headed up by Cooper. On her first visit to Winter’s, Cooper was told that during World War II, as part of the Dig For Victory campaign, the studio gave many of its large glass-plate negatives to the public. The sheets were made into greenhouses.

“The image of negative greenhouses across the city was an enchanting one, and one that had to be remade,” says Cooper. She used glass-plate negatives that had been seriously damaged over the years, water stains and scratches melding with the smiling faces of an earlier time, rebuilding the hexagonal greenhouses in a gallery setting, the panes now dramatically scaled portraits.

“People, Places and Things draws on this archive to show how this striking and surprising collection forms an important record of the interwoven personalities, industries and changing landscapes of the city,” says Greg Hobson, former curator of photographs at the National Media Museum, who is curating the show for Derby Museums.

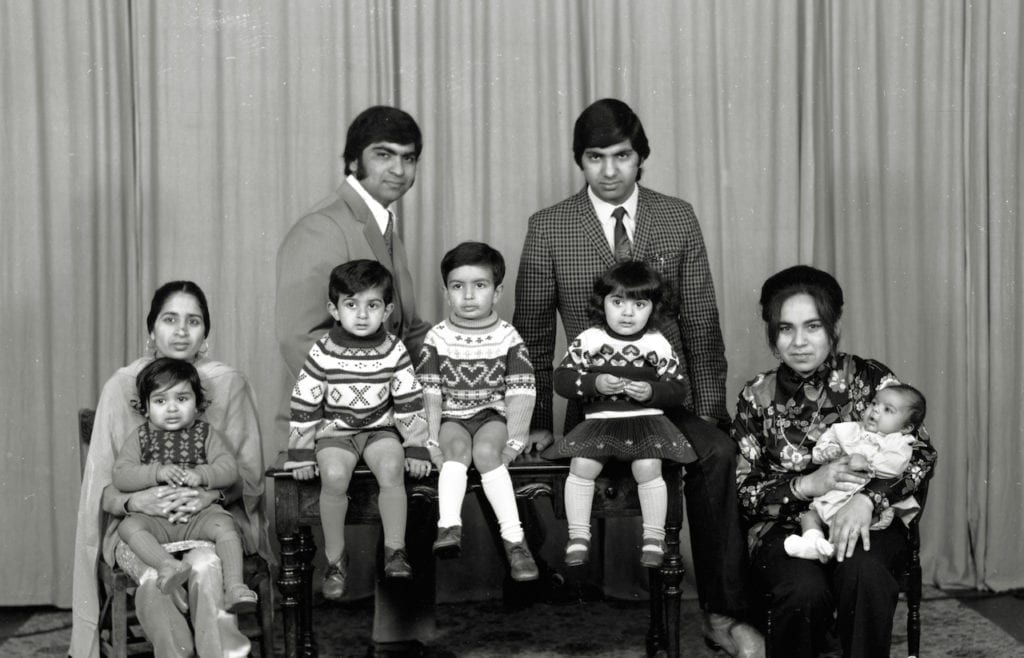

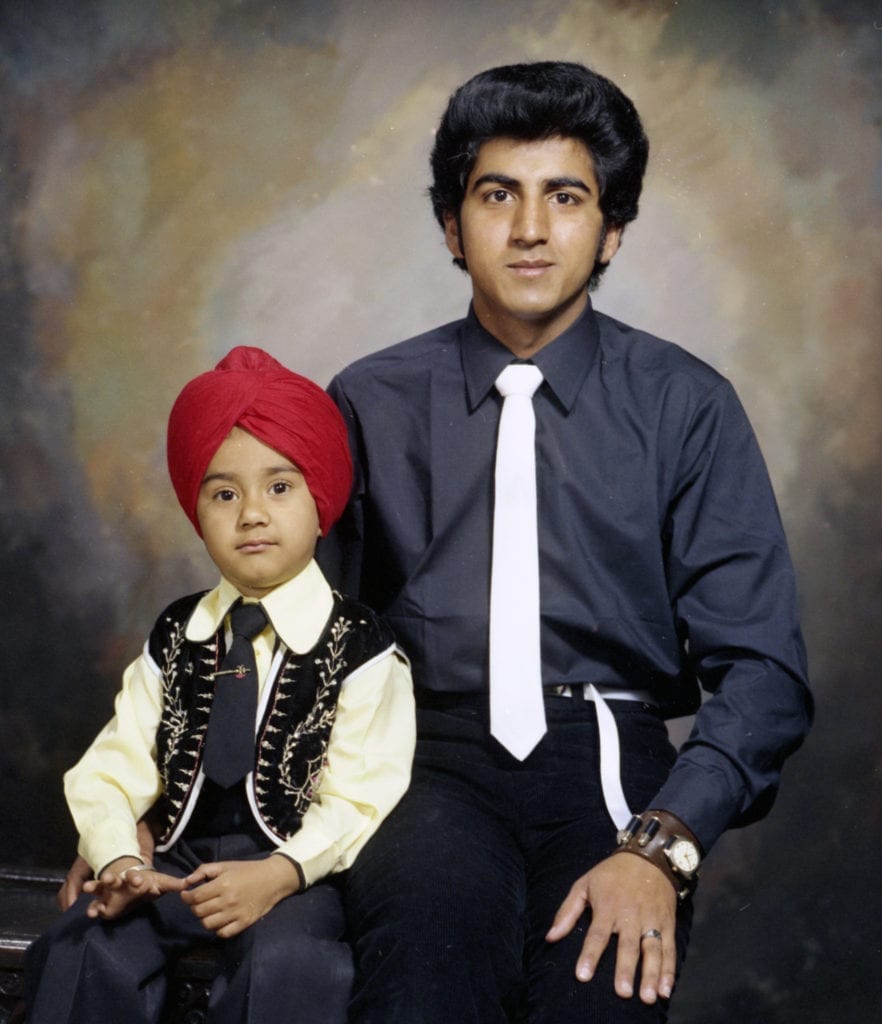

“Studio portraits are a map of sitters’ aspirations and self-image: a photograph of a man gripping the front paws of his dog, trying to keep it still for the long exposure; a boy with no legs stares defiantly at the camera while a young girl plays in the background. Specially moving are the photographs of families that can be traced through the visits made by children, parents and grandparents, each generation returning to be recorded for posterity by the Winter photographers.”

As part of her residency, she learnt how to make and shoot on glass – a photographic process from the 1860s that has been almost entirely lost. “Dating from the late 1800s to mid 1900s, the large glass-plate negatives depict everything from theatrical performances and images of industry to studio portraits, street scenes and more.”

Although little is known about most of the subjects, “the anonymous portraits from the WW Winter collection show a historic snapshot of the city,” asserts Cooper.

One particular passage of history has proved very fascinating. During World War I, German POWs were interned at a camp set up at nearby stately home, Donington Hall. It was dubbed ‘the Gentleman’s War’ and the captured soldiers were treated with dignity. Winter’s chief photographer at the time travelled to the camp and took portraits of the soldiers, before asking each one to write down their address. Once back at the studio, he dutifully sent each portrait to the designated address as a way of showing the soldiers’ families that they were safe and being cared for, behind enemy lines.

People, Places and Things: the WW Winter’s Archive is on show from 23 March to 23 April at Derby Museum derbymuseums.org Format International Photography Festival opens this weekend, and the exhibitions are on show until 23 April. www.formatfestival.com

This interview was first published in BJP’s March 2017 issue, which was themed Habitat and produced in partnership with Format International Photography Festival. Back issues can be bought from www.thebjpshop.com