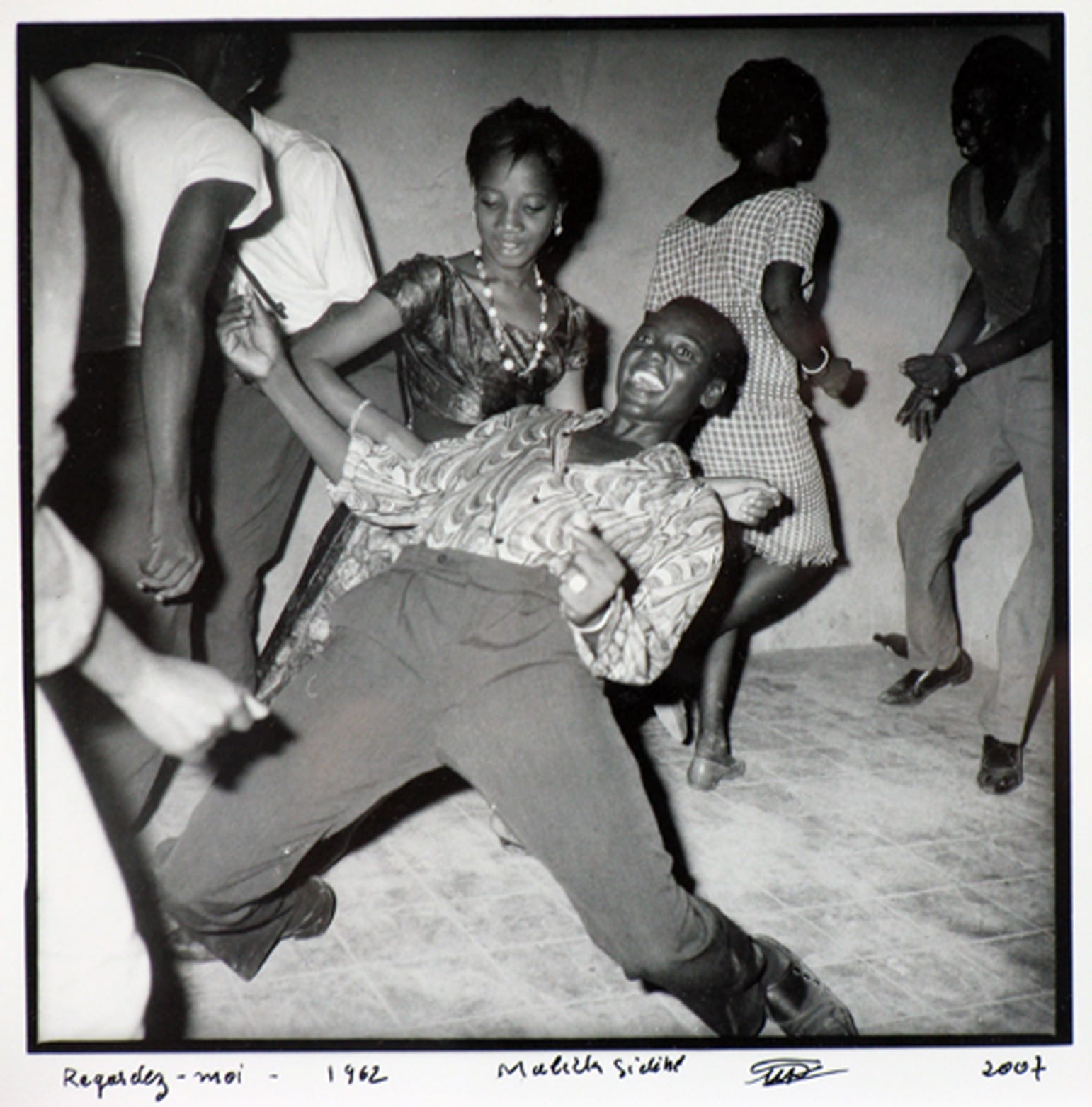

They’re dressed, fantastically, in white, but they couldn’t be more black. They’re holding hands, in the midst of a dance, and most probably a courtship. It’s late in the night. Music is playing. They look flushed, happy. They couldn’t be more alive. And they are about to celebrate their independence.

In Bamako, the capital of Mali, in the late nineteen fifties, where this photo was taken, the boys would form gangs with over the top names. They’d belong to the Wild Cats, or the Black Socks.

In a country still under the control of an imperialist French government, in which the natives of what was then French Sudan were afforded virtually no civil liberties, and in which conservative ethnic and religious concerns still exert a powerful pull on the country to this day, these young men would dress snappily, head into the night, and spend it engaging in the joyous pursuit of the opposite sex.

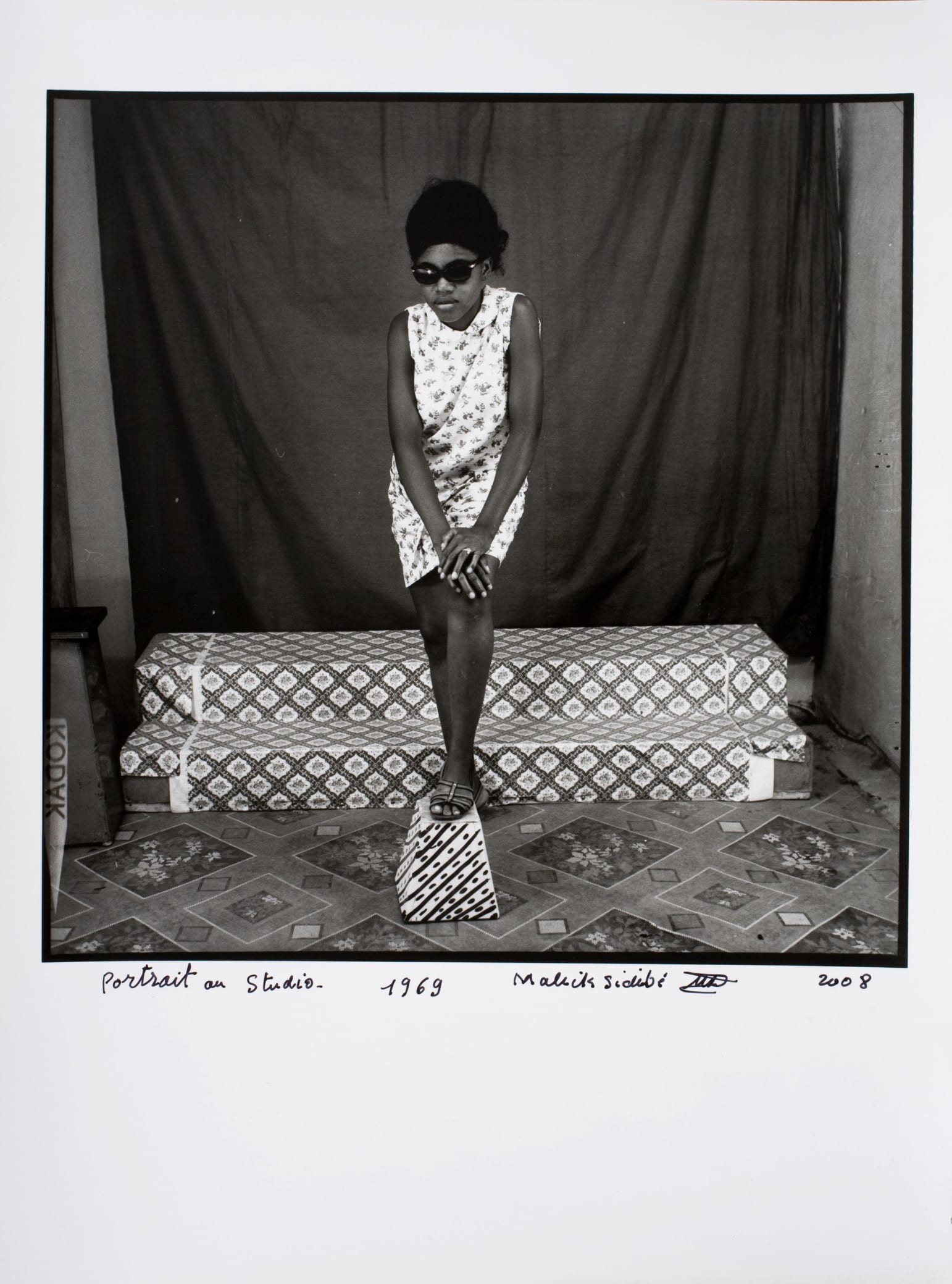

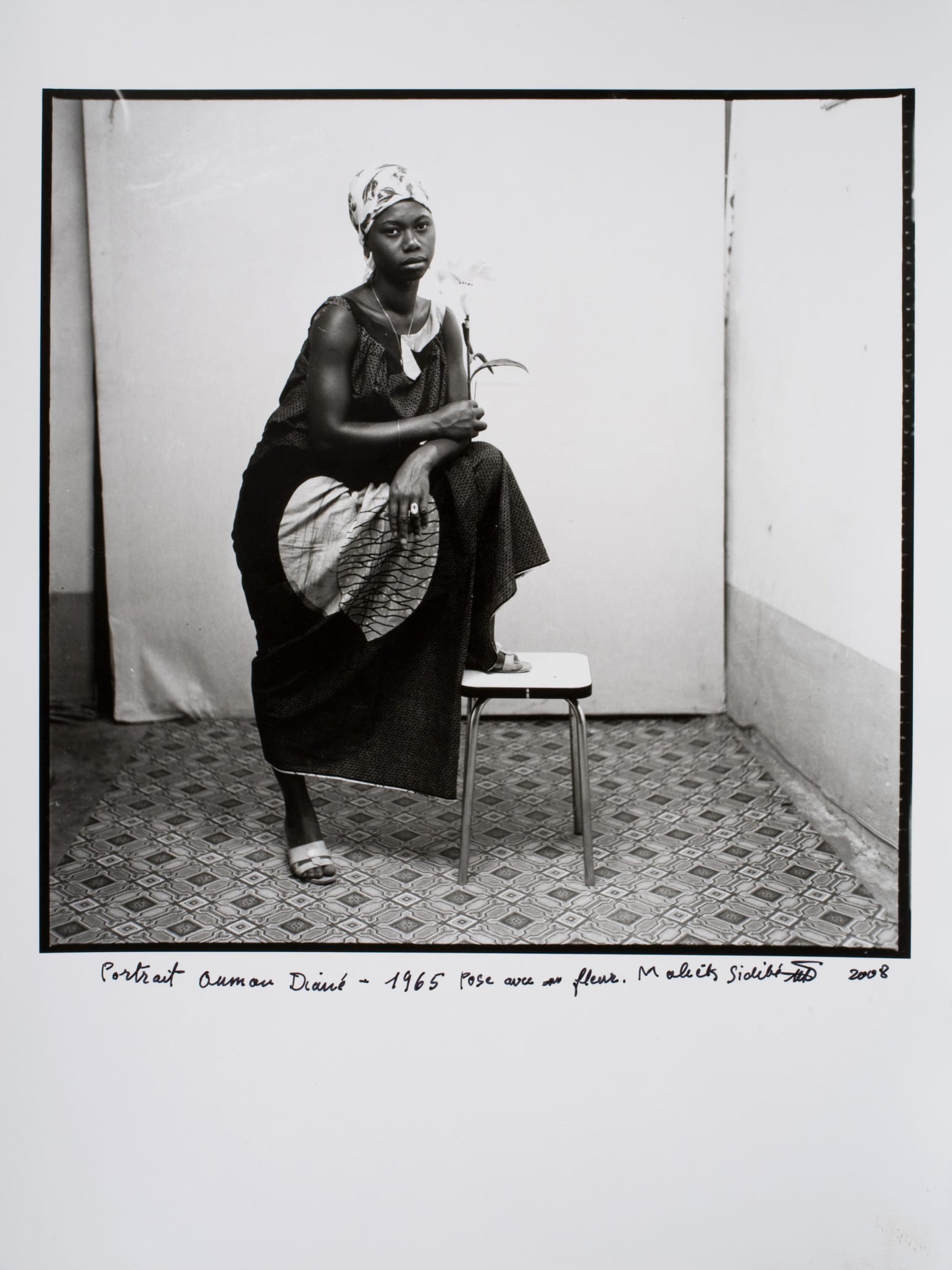

Existing beyond closed-doors, Malick Sidibé was the only photographer to capture this new, revolutionary youth movement. They became zeitgeist images, not just for that specific generation of Mali, but for the African continent as a whole.

Born to a peasant family in what was then French Sudan in circa 1935, he would leave his shepherding duties of the family’s flock at the age of 10 to study at a colonial school at which he was one of very few non-white students.

Nevertheless, he secured a position at École des Artisans Soudanais in Bamako in 1952. Soon after, Gérard Guillat, a French ‘society’ photographer who called Mali his home, asked him to become his apprentice.

Sidibé would worked by day for Guillat. He wasn’t allowed to use Guillat’s cameras. He’d merely assist, tend to customers, work the shopfront.

But he learnt from a distance. And at night, with a bicycle and his first camera, a small, portable Brownie Flash, he would tour the nightclubs of Bamako, from one to the next, taking pictures.

He’d sometimes take in five clubs a night, and then he would return to Guillat’s studio and, at six in the morning, develop the night’s work in the darkroom.

Guillat would spend his time with the imperialists, photographing the nicer parties, the weddings and social occasions in which black people were only invited to wait and serve. Under his tutelage, and without his full knowledge, Sidibé was photographing the real subjects of the city. He became known “the Eye of Bamako,” the man about town whom everyone knew, and everyone would model for. Two years later, in 1958, Sidibé went solo, opening his own studio, Studio Malick.

In 2007, he became the first African winner of the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the Venice Biennale.

In a 2010 interview with John Henley in The Guardian, Sidibé said: “To be a good photographer you need to have a talent to observe, and to know what you want. You have to choose the shapes and the movements that please you, that look beautiful.

“Equally, you need to be friendly, sympathetic. It’s very important to be able to put people at their ease.

“It’s a world, someone’s face. When I capture it, I see the future of the world. I believe with my heart and soul in the power of the image, but you also have to be sociable. I’m lucky. It’s in my nature.”

Now, 60 years since those halogen days in Bamako, Sidibé has died of complications of diabetes at the age of 80.

Find out more about Sidibé here.