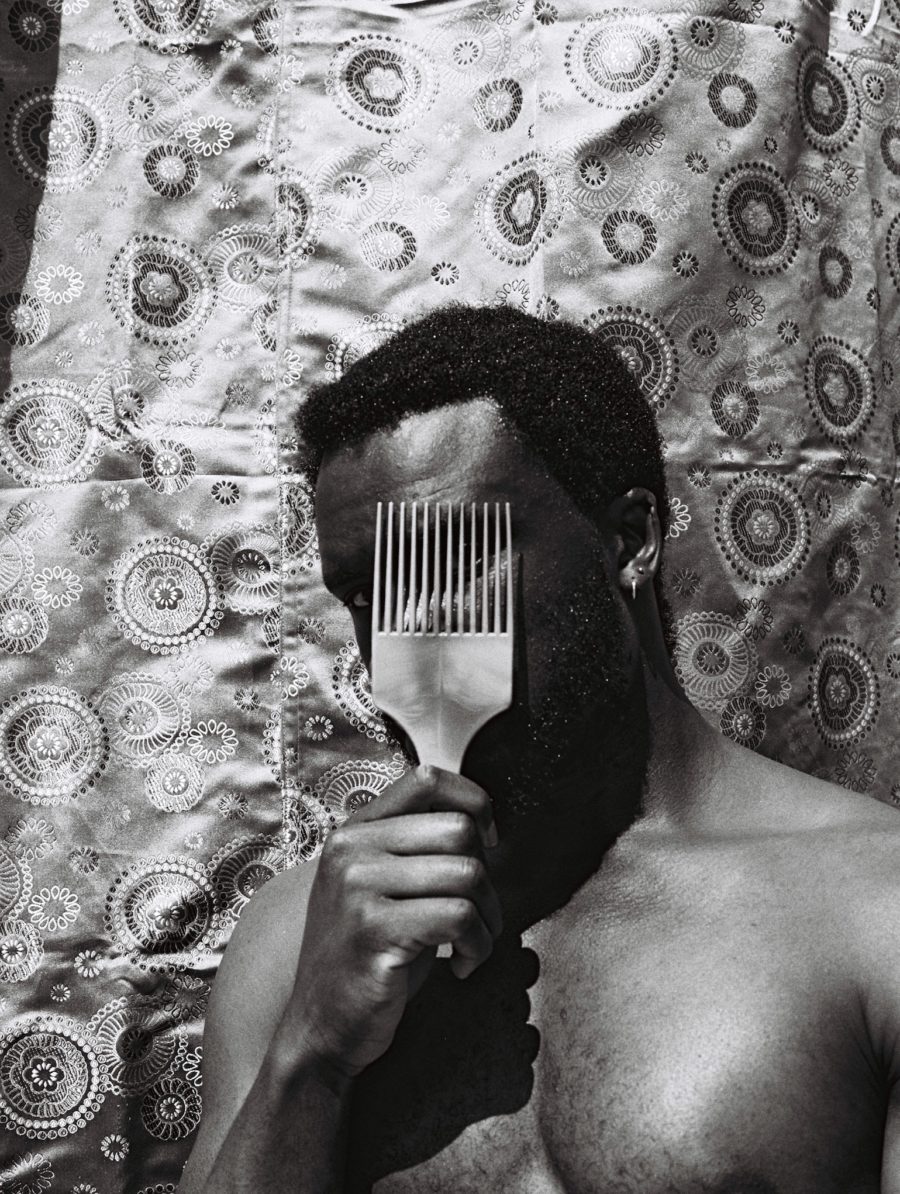

The Afropean author is back with a touring show, curating working-class photographers to present an alternative reading of class aesthetics

The Afropean author is back with a touring show, curating working-class photographers to present an alternative reading of class aesthetics

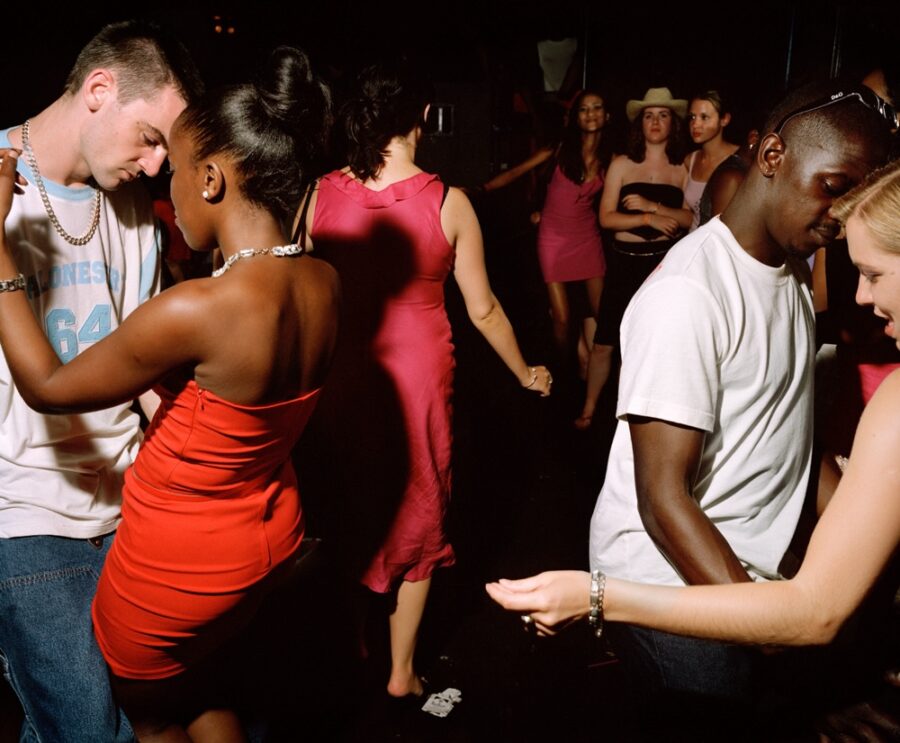

Creative duo and club stalwarts Martin Green and James Lawler take a utopian yet realistic look at 90s Queer nights in Britain, at Open Eye Gallery

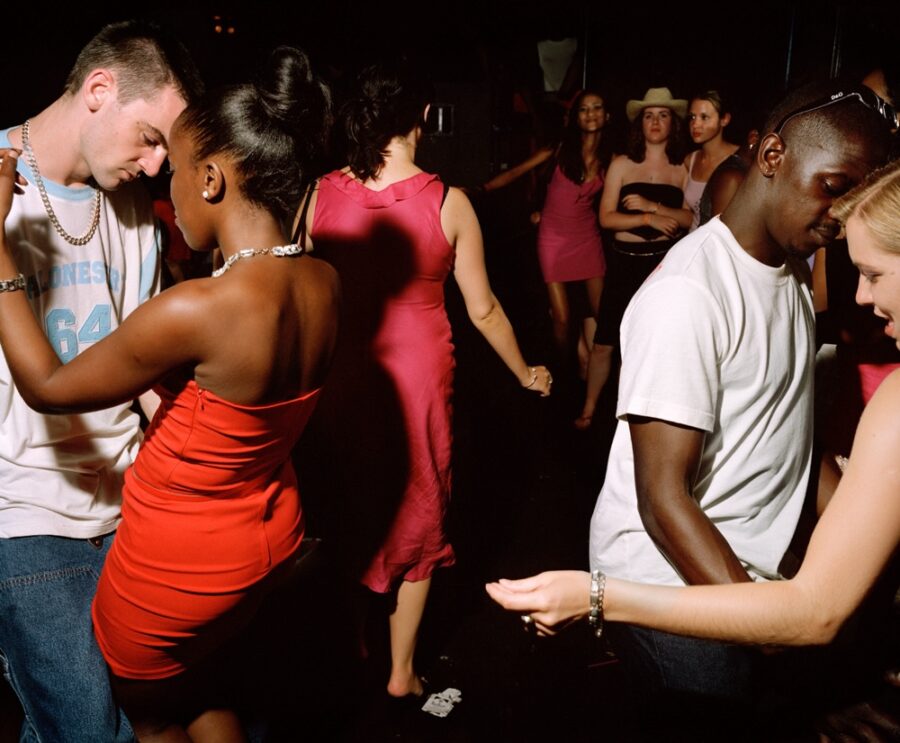

Marilyn Stafford: A Life in Photography spans the pioneering fashion photographer’s career across several continents, whose work often surprised and challenged her own sensibilities

With Portrait of Britain 2021 open for entries, a selection of this year’s judging panel consider why Portrait of Britain is important today — and crucially, how artists can stand out from the crowd

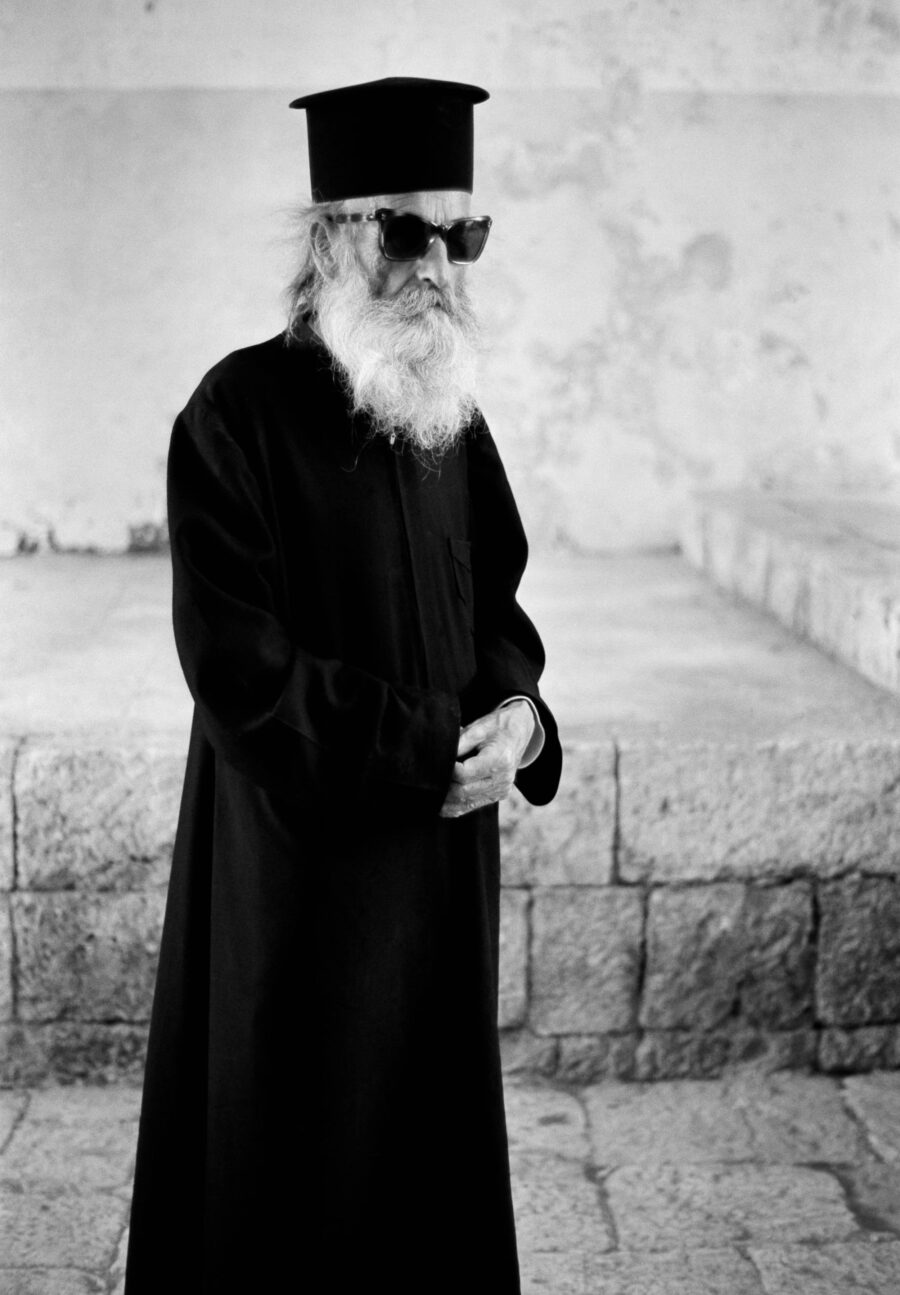

“It felt like a poignant opportunity to reflect on the contribution that Black people continue to make to British culture”

Johny Pitts, the recipient of the fellowship, will create a new body of work reflecting on Black Britishness through its myriad manifestations across the UK

Czesław Siegieda’s documentation of a generation of Poles who arrived in the UK as refugees has remained largely unseen since the 1970s. Now, 40 years later, his unique record is published in a photobook