LUMIX Stories for Change is an ongoing collaboration between British Journal of Photography and Panasonic…

LUMIX Stories for Change is an ongoing collaboration between British Journal of Photography and Panasonic…

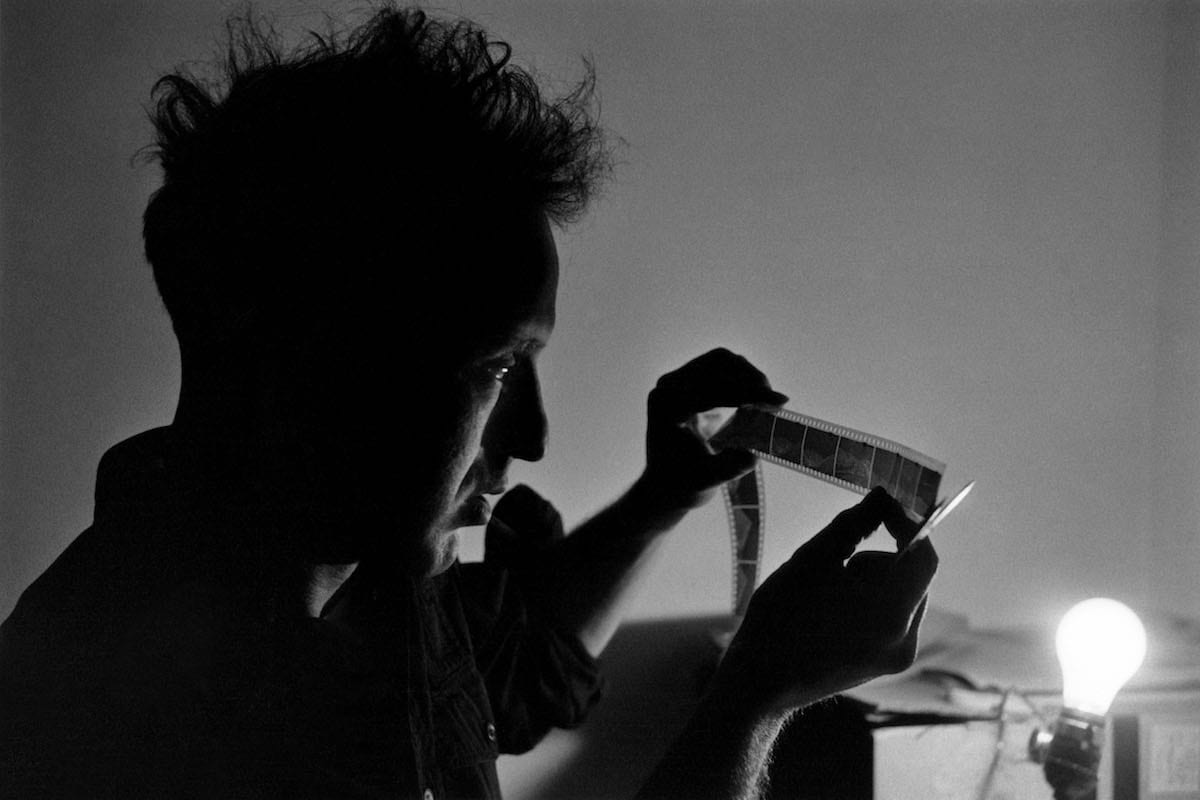

Robert Frank’s The Americans greatly influenced the course of 20th and 21st-century photography. His contemporaries, and those who followed, reflect on the enduring significance of his work

In his latest project and soon-to-be book, George Georgiou finds anonymity and intimacy along the roadside of American parades

LUMIX Stories for Change is an ongoing collaboration between British Journal of Photography and Panasonic…

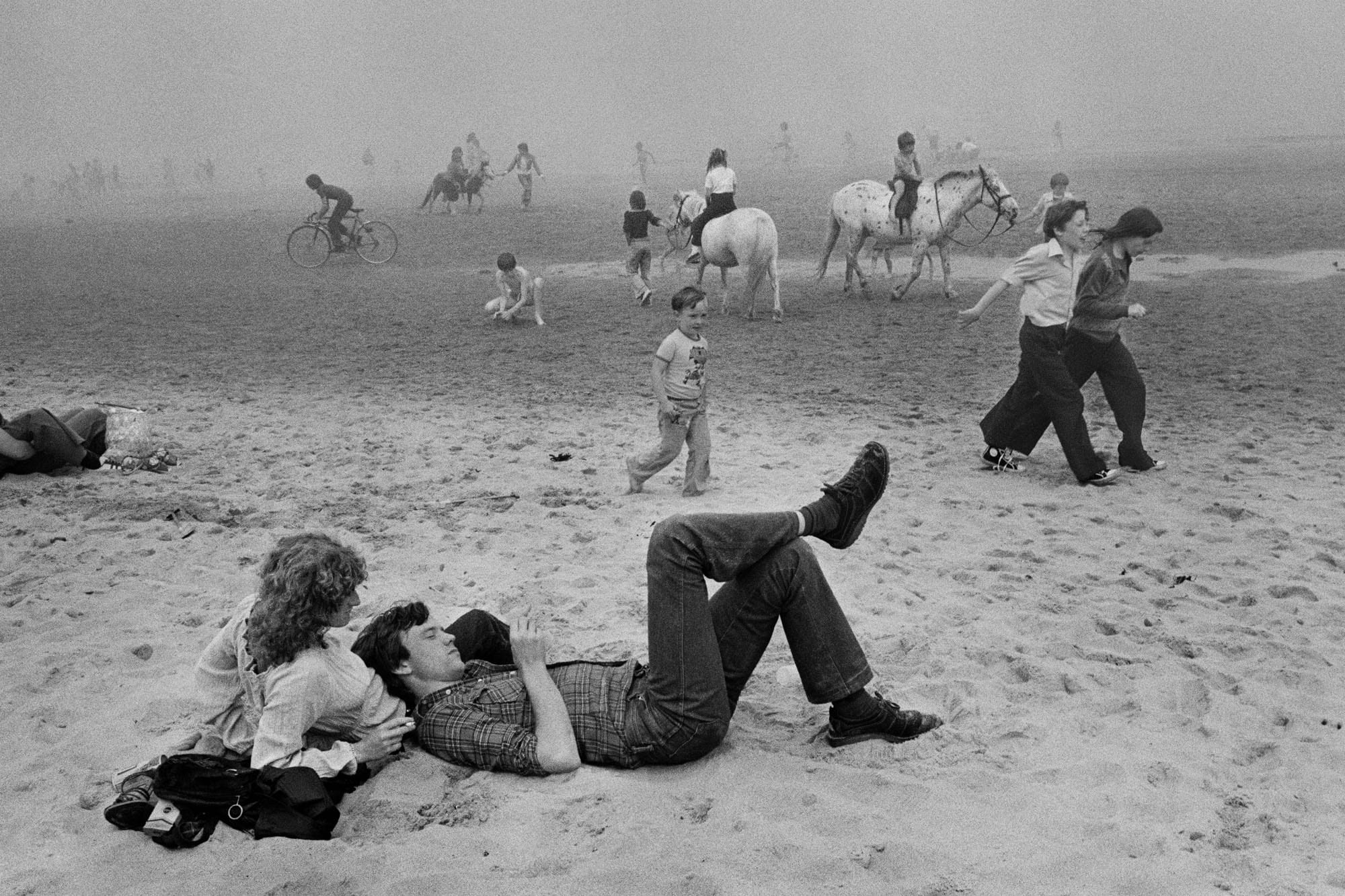

“Life was good, and perhaps my happiness was reflected in the way I photographed there,” says Markéta Luskačová, as she presents her work from the late 1970s in a new exhibition and book

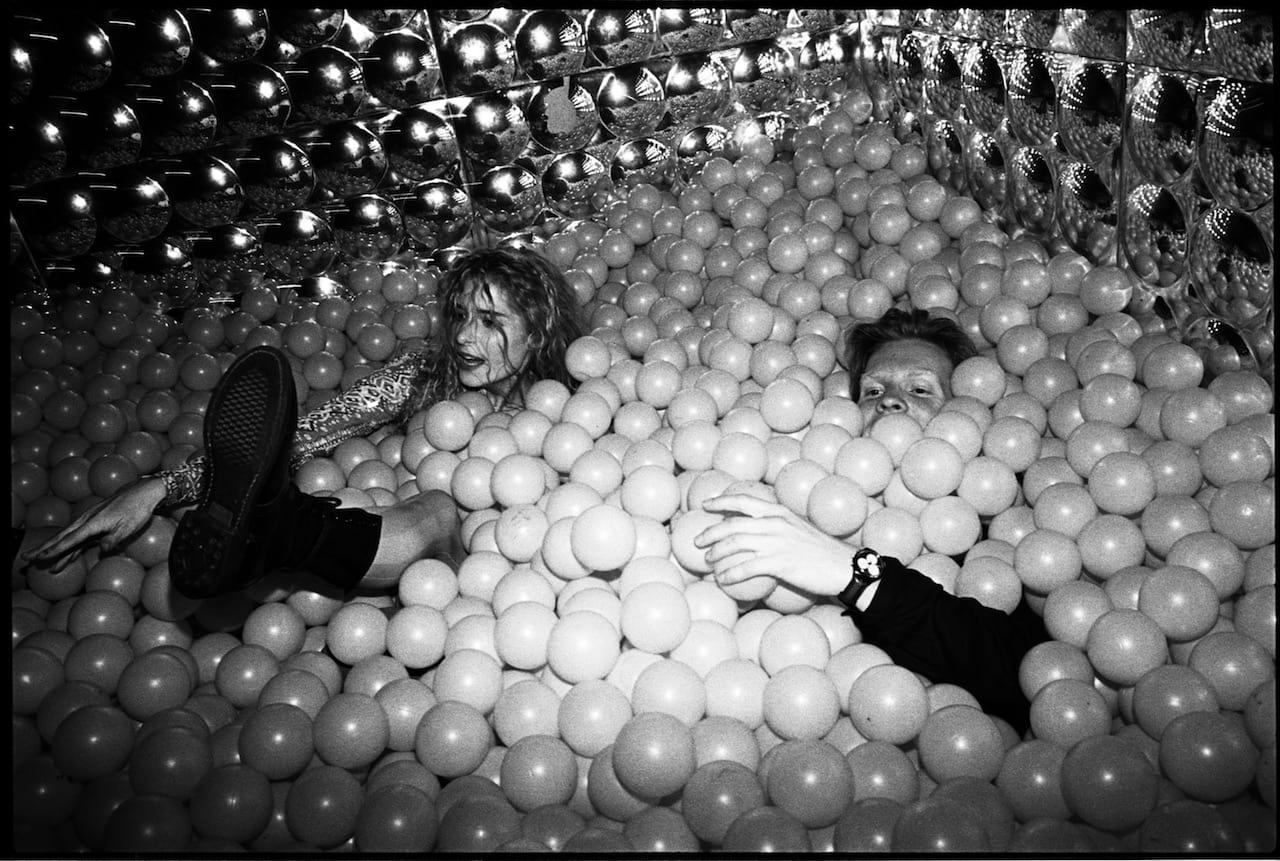

In an upcoming book, former Club Kid Walt Cassidy chronicles the 90s New York party scene with a curation of over 500 images by 18 artists

Li Yang returned to photograph his hometown, an abandoned city known as 404, which was once China’s largest nuclear base

Identity politics looms large for many young Turkish photographers. Not least Cansu Yıldıran, whose work explores her roots in the Kusmer highlands, and her adopted community in Istanbul

Land grabs, forced displacement, Maoist rebels, state executions… Central India’s 50-year conflict is virtually unknown outside the Subcontinent, and Poulomi Basu’s investigation of this hidden war defies an easy reading