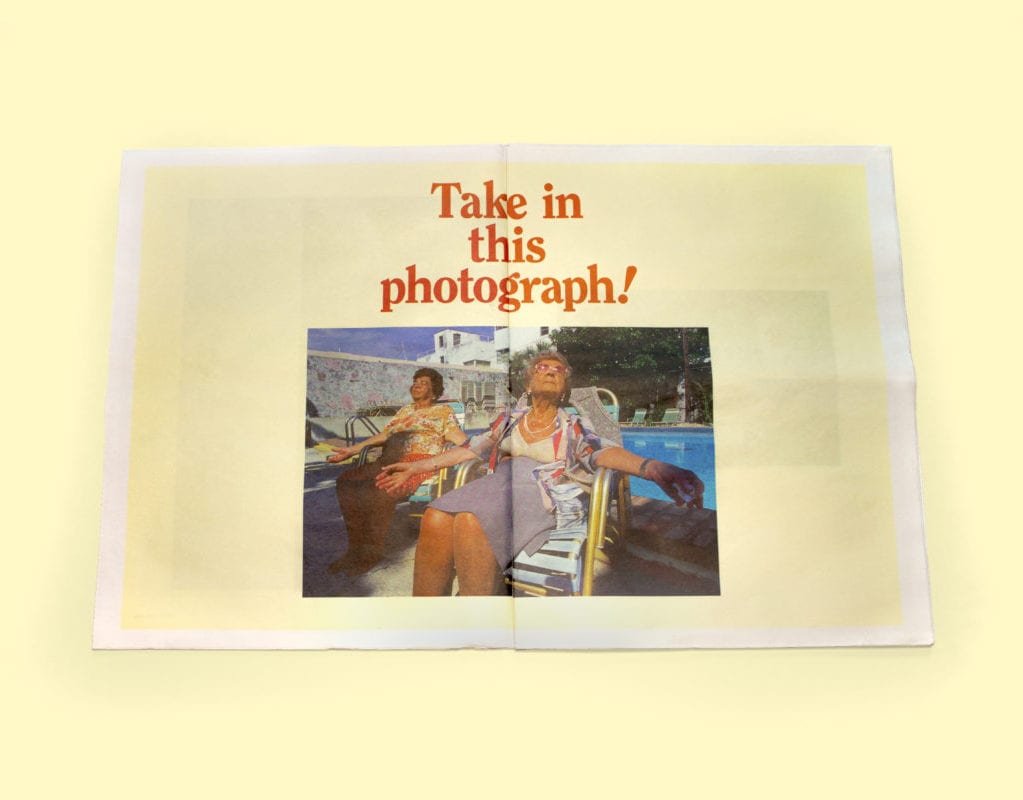

During summer 2015, you couldn’t open a paper without seeing photographs of the Syrian refugee crisis – the worst such crisis since the Second World War.

The photographs are heart-wrenching, showing rickety rafts piled high with men, women and children, desperate to make their way across the sea to Europe; or these travellers arriving on Greek beaches, drenched, tearful, and exhausted. Depending on the publication, the articles accompanying the pictures ranged from empathetic to sensational.

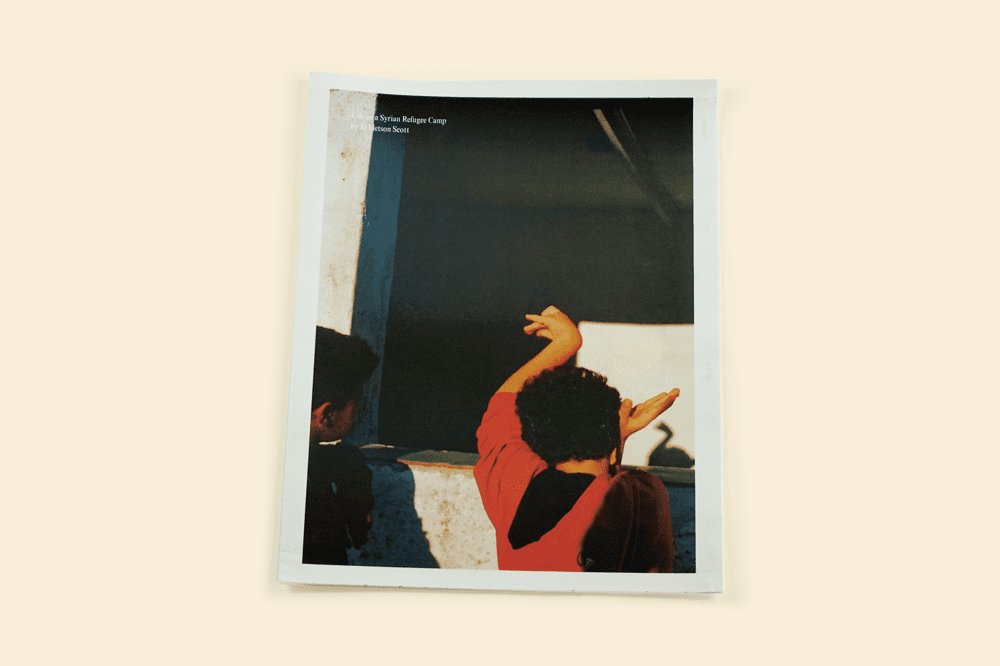

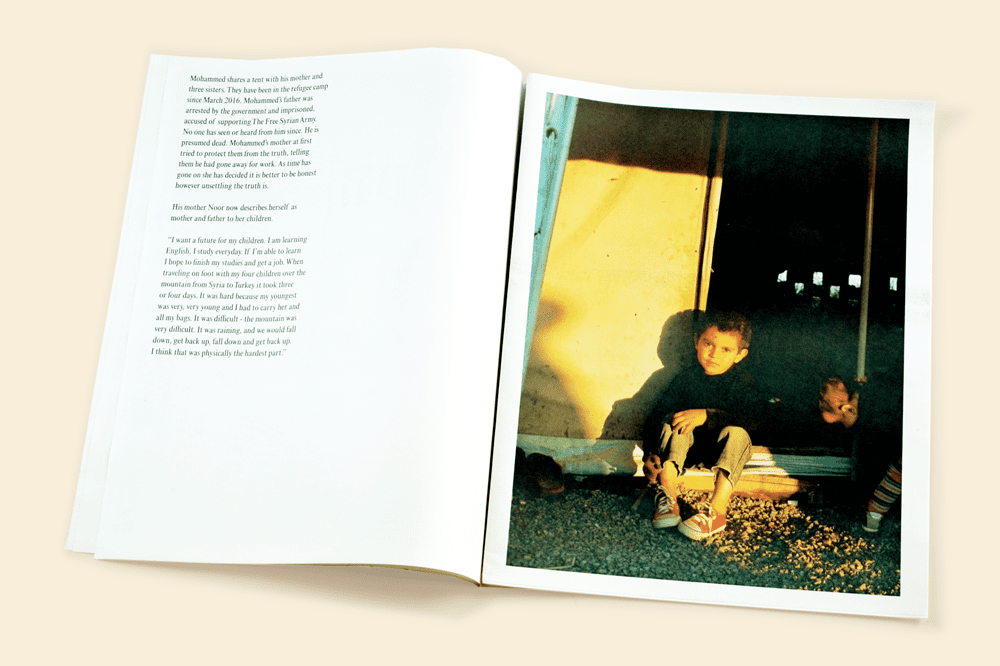

“At the time there were 800 people, half of whom were children, living in tents, which I found quite shocking” says Metson Scott. “They’d made it across the water and a lot of them had made it as far as Macedonia but then the borders closed. I wanted to look at the people who were trapped, waiting to be processed, in Greece.”

“They can’t be self-sufficient, even though they want to be. They weren’t allowed to make fires so they weren’t able to cook their own food. They were waiting for food. They were waiting for donations of clothes, waiting to get their phones charged.”

Metson Scott was led by each person whose story she was documenting, but she was also keen to address certain issues that came up in press about refugees – such as why so many young men travel alone. “Often because the family can’t afford to send everyone, they have to make the heartbreaking decision who to send – and it’s usually a male because they’re about to be conscripted to a military they don’t want to be part of.”

Metson Scott has always questioned received media narratives. Her book The Grey Line, a study of British and American soldiers who have spoken out about the Iraq war and the repercussions they faced, was published in 2013 by Dewi Lewis to great acclaim. Since then she has continued to produce personal work such as Borderland, on the Scottish referendum; Gym Boy, following a young Olympic hopeful; and Momas, about the physicality of new parenthood, while shooting fashion and editorial commissions, and working as photo director at Pleasure Garden Magazine.

“It was nice to be able to publish some of the words with the story but it was really an awareness and a visual tool to tie in with the auction,” she says. “I like the fact that it’s fast, you can be less precious in a way. I’d definitely do it again.”

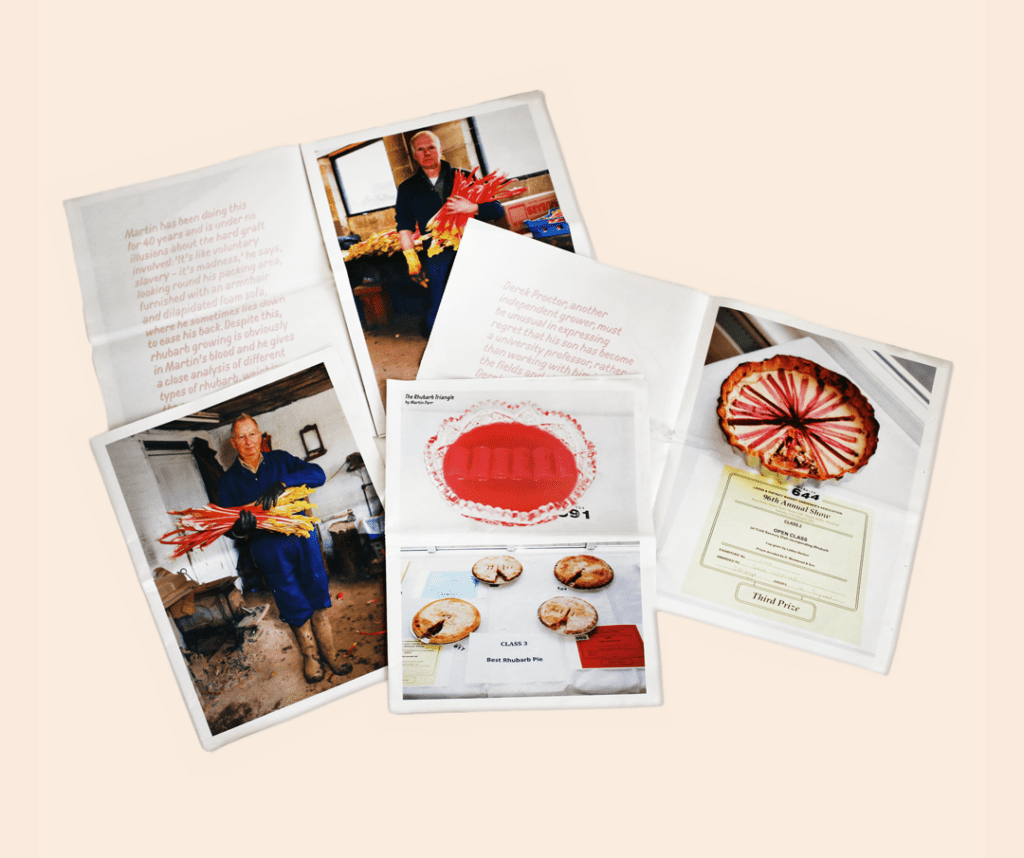

Life on a Syrian Refugee Camp is one example of the many ways photographers have published their work with Newspaper Club. Martin Parr’s The Rhubarb Triangle was made to accompany an exhibition of work by the same name which was commissioned by Hepworth Wakefield. In true Parr style, the paper is a wry, affectionate insight into a quirky section of British life.

For photographers the appeal of newsprint is that it offers “something eye-catching and different that’s also cost effective,” says Ward, who is continually surprised by inventive approaches they take. “It’s something they’re very familiar with but they’ve not always had a chance to print on it.”

And as for Newspaper Club, their mission is clear: “We’re trying to keep newspapers – and print – alive.”

Working on a new project that you want the world to see? Then maybe you should think about publishing it as a newspaper. Visit Newspaper Club’s website to find out how.