The French-Polish photographer sheds light on the experience of 15 individuals who took a leap of faith and fled the dictatorship, in search of a better life in South Korean

The French-Polish photographer sheds light on the experience of 15 individuals who took a leap of faith and fled the dictatorship, in search of a better life in South Korean

LUMIX Stories for Change is an ongoing collaboration between British Journal of Photography and Panasonic…

LUMIX Stories for Change is an ongoing collaboration between British Journal of Photography and Panasonic…

LUMIX Stories for Change is an ongoing collaboration between British Journal of Photography and Panasonic…

Questioning the ethics of his own images from North Korea, the French photographer asks whether it is permissible to enjoy an image knowing that the beauty could be masking the suffering of a nation

In November this year, Jimei x Arles International Photography Festival, the sister festival to the renowned Rencontres d’Arles, celebrated its fourth edition in Xiamen, in China’s Fuijan province. With an overall view to “serve as a cultural exchange between France and China”, the annual event hopes to also raise the profile of photography in China by providing a meeting place for professionals in the field and providing a platform for emerging photographers to showcase their talent.

“It is a matter of promoting an idea of culture and art, that is both creative and popular, open to greater audiences but also a site for encounters between creatives,” explains Victoria Jonathan, one half of the creative direction team alongside Bérénice Angremy. “It is also an opportunity to nurture an artistic dialogue between Chinese and European artists and audiences. Ideas travel with exhibitions and art projects. For Arles, it is also an opportunity to have a foot in China and grow a deeper knowledge of the Chinese and Asian photography scenes.”

It is difficult to unravel, in many of the stories that Max Pinckers tells, where fiction became unstuck from fact. Or how the characters in his photographs can look back out at the world so boldly, shake their heads at reality as most people see it, and tell stories that fly in its face. But for the Brussels-based photographer, the six curious individuals in his latest book, Margins of Excess – including a boy who compulsively hijacks trains, and a private detective with prosthetic hands – lead the way to understanding documentary photography’s role in the ‘post-truth’ era.

One such character, an American amateur inventor with a mane of silken hair, sat at the kitchen table of his home in Dunnellon, Florida and told Pinckers that he believed he had become the media’s new Osama bin Laden. “My name is Richard Heene. A few years ago I got into a bit of trouble,” said the forty-something showman, detailing the events that led him to end up behind bars.

Belgian photographer Max Pinckers has won the prestigious Leica Oskar Barnack Award with his series Red Ink. He receives €25,000, plus a Leica M camera and lens.

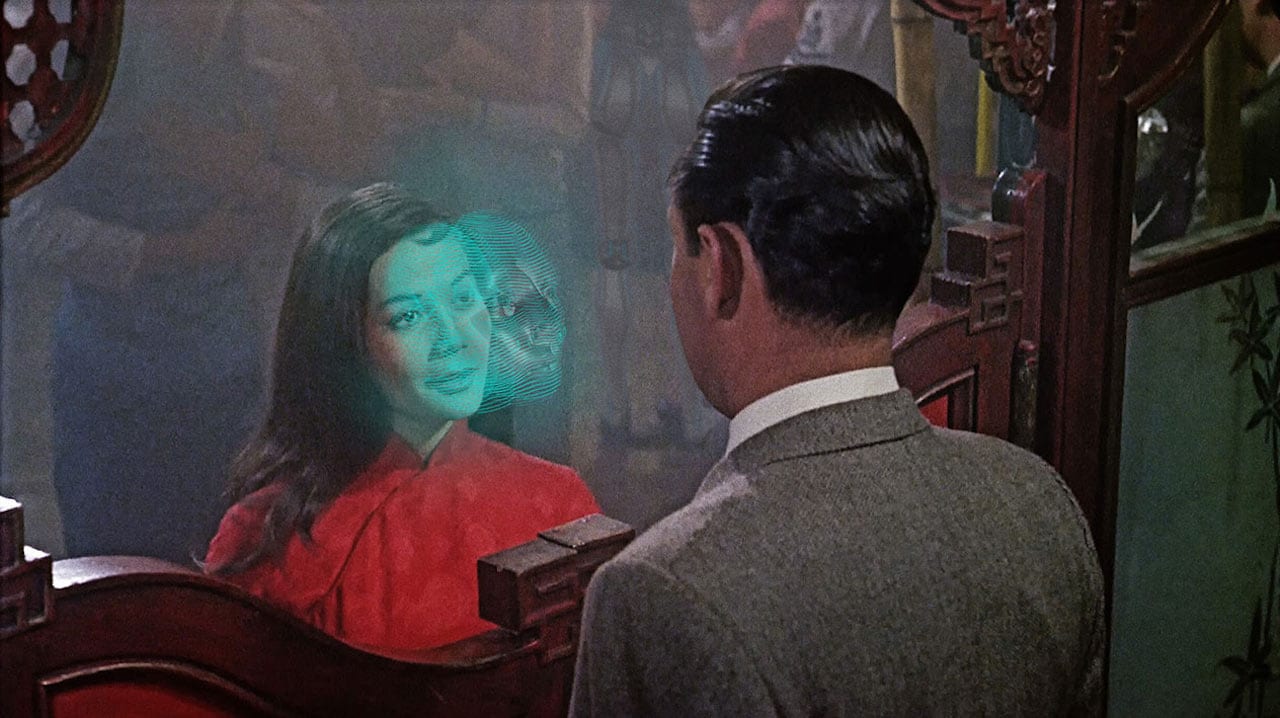

Red Ink was shot in North Korea while Pinckers was on assignment for The New Yorker magazine, accompanying journalist Evan Osnos on a four-day trip in August 2017 – the height of the propaganda war with the US. Pinckers’ access to the country was heavily stage-managed by the North Korean government, which carefully set up scenes for him to photograph. Knowing that this would be the case, Pinckers shot the images with a flash, creating a sense of the artificial that tipped the scenes presented to him into the surreal.

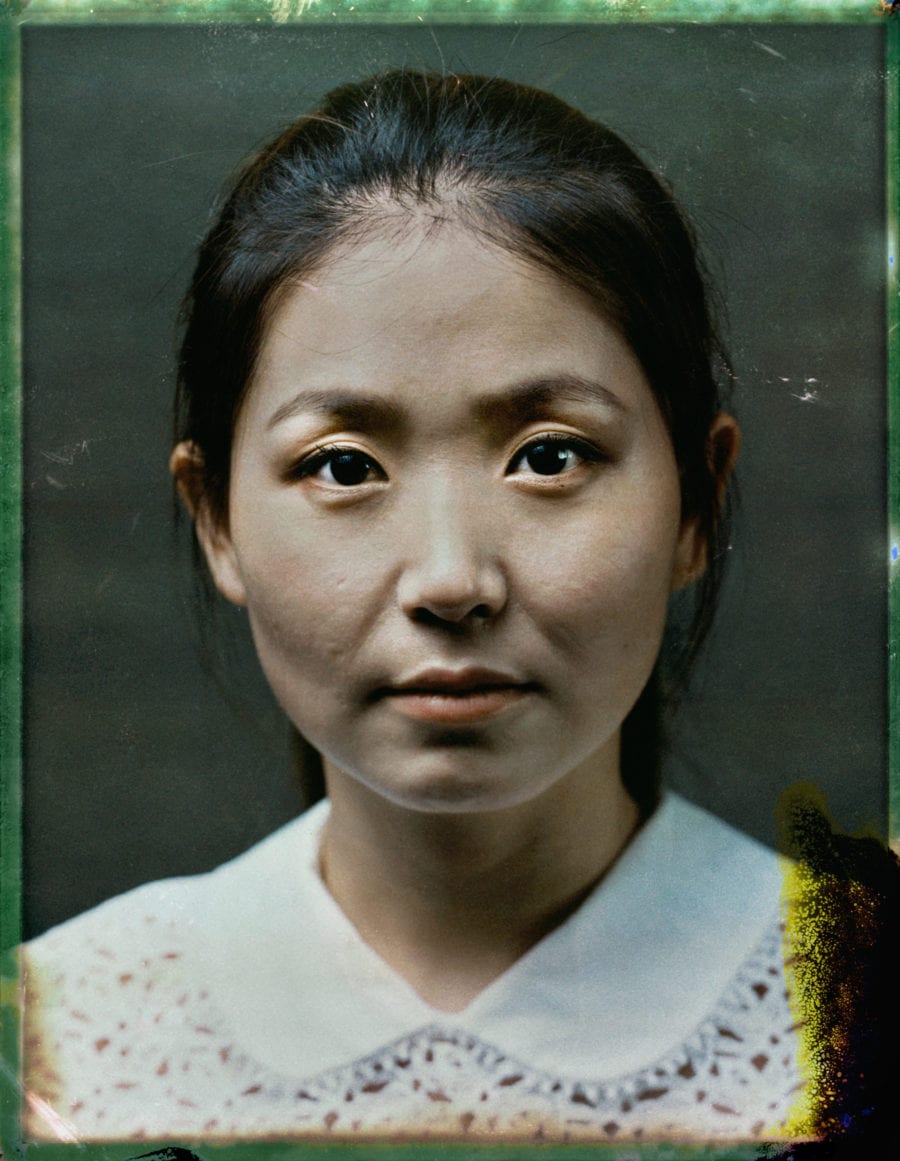

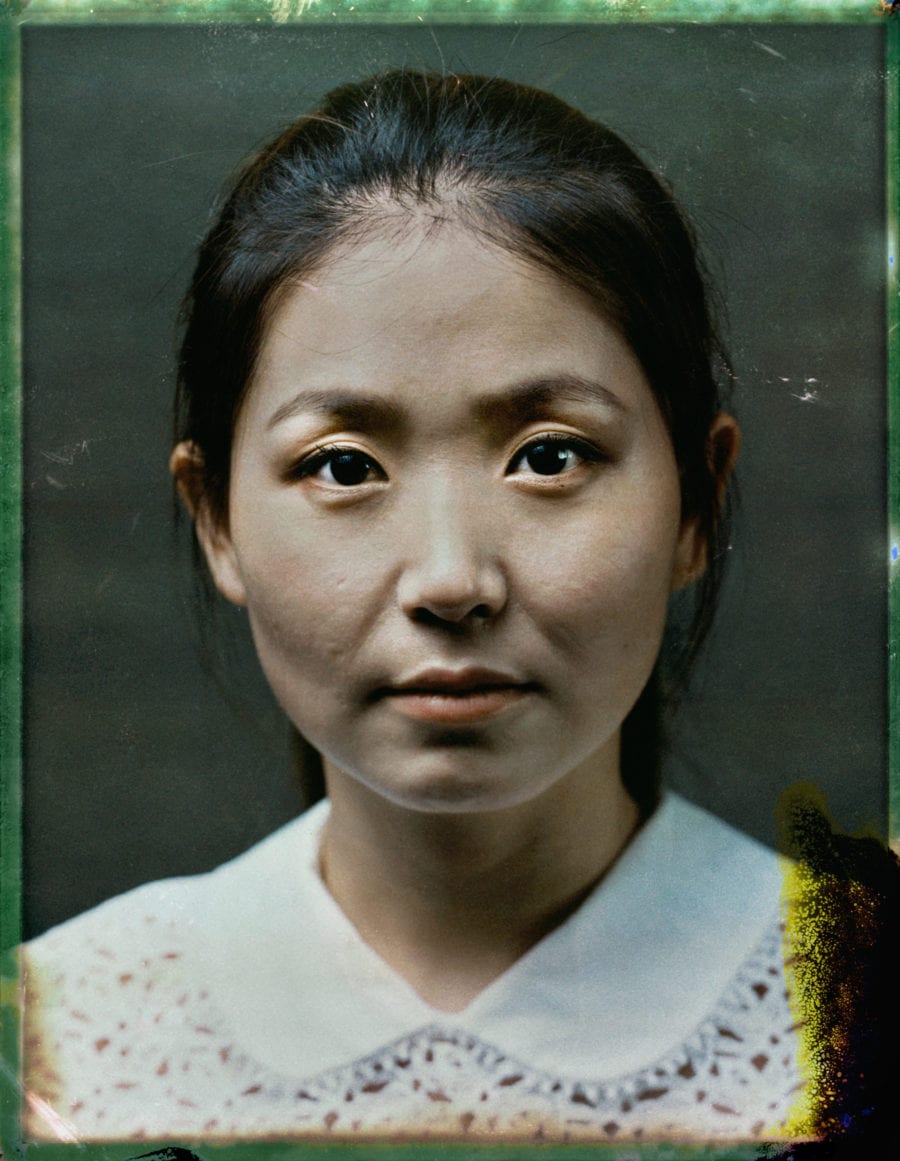

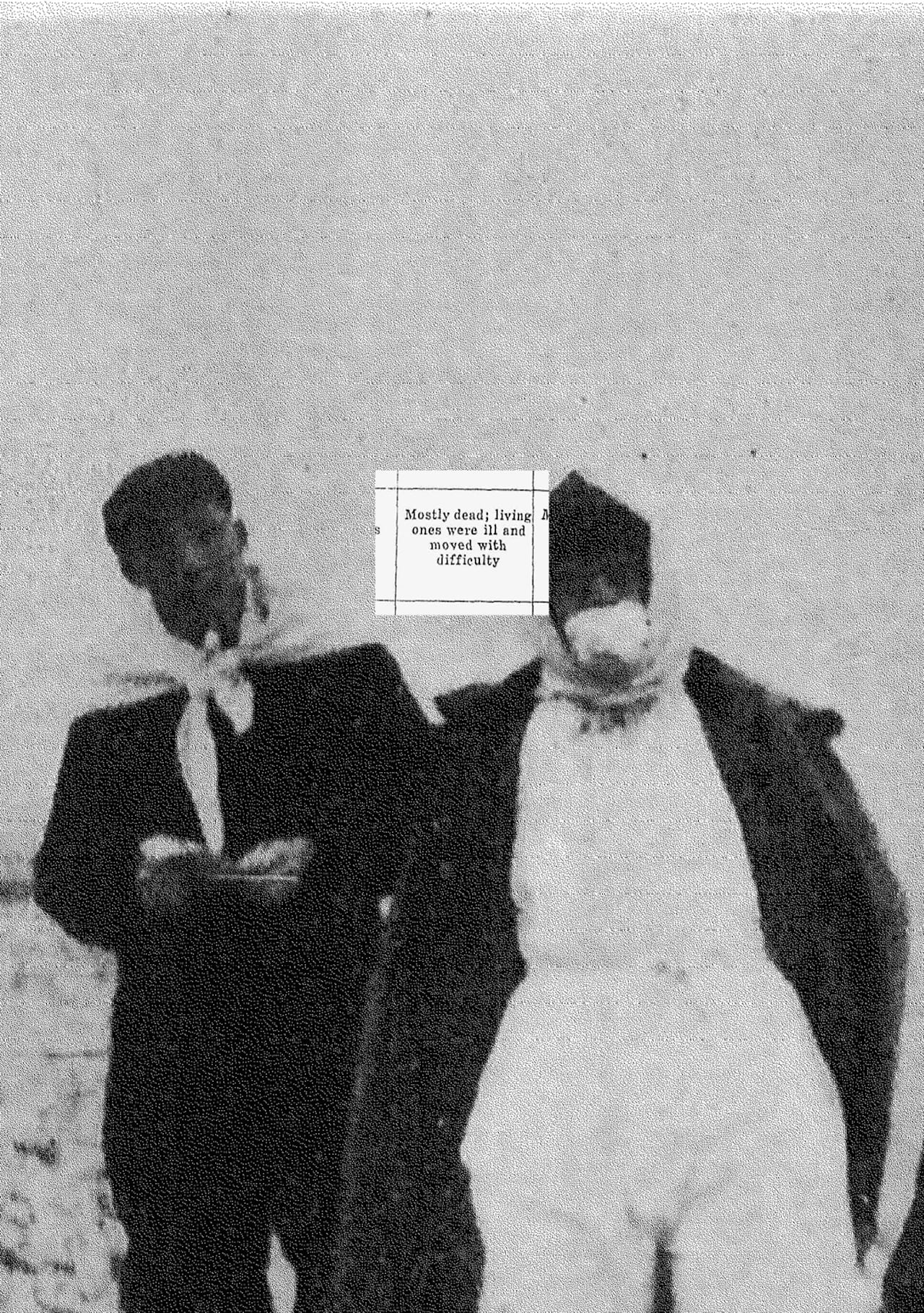

“There is a term to describe the cultural ache that Koreans go through: Han. A complex intermingling of historical, collective and personal sorrow, acceptance of a bitter present, and a hope of a better future.” Introduced to the term by a North Korean defector, Herman Rahman decided to adopt it as the framing concept for his project of the same name.

Han traces the collective history of the notoriously closed regime of the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea, relying largely on archival imagery and found text to probe at the borders of a near-impenetrable subject. The work is an interrogation, not only of the secrecy of the North Korean state, but also of the nature of photography itself.

It’s disconcerting to think how years of work and effort, of countless hours spent practising and honing a skill, can be wrenched away from any of us in just a few minutes of misfortune. It’s also, for any of us used to good health, troubling to consider how reliant we are on the basic functionality of our bodies. A photographer, for example, needs to be able to hold a camera, to have the strength to frame a shot and time the click of the shutter in the heat of the moment. Shorn of that basic ability, what are we left with? Early one morning in May 2015, Sim had to face that exact question.

She was on assignment for a French newspaper, travelling to the Tumen Economic Development Zone, a government-owned complex of Chinese factories on the edge of the border with North Korea. Tumen employed North Korean labourers who, with state sanctioning, would be sent to live and work in the economic zone. The brief was to capture how North Korea and China trade. This place seemed like the perfect microcosm for that complex relationship – the makings of great pictures.

Entering Tumen with her driver and colleagues from Le Monde, she failed to spot a sign that read: “No smoking, photography, or practising driving”. As they approached the factories, the car passed a small group of women in black jumpsuits, knelt by the roadside picking weeds from the ground. Sitting in the driver’s seat with the window wound down, Sim instinctively raised her camera and fired off a couple of shots. “Almost immediately, the women turned around, ran towards the cab, and reached into the car,” she wrote in an article for ChinaFile, recounting events.