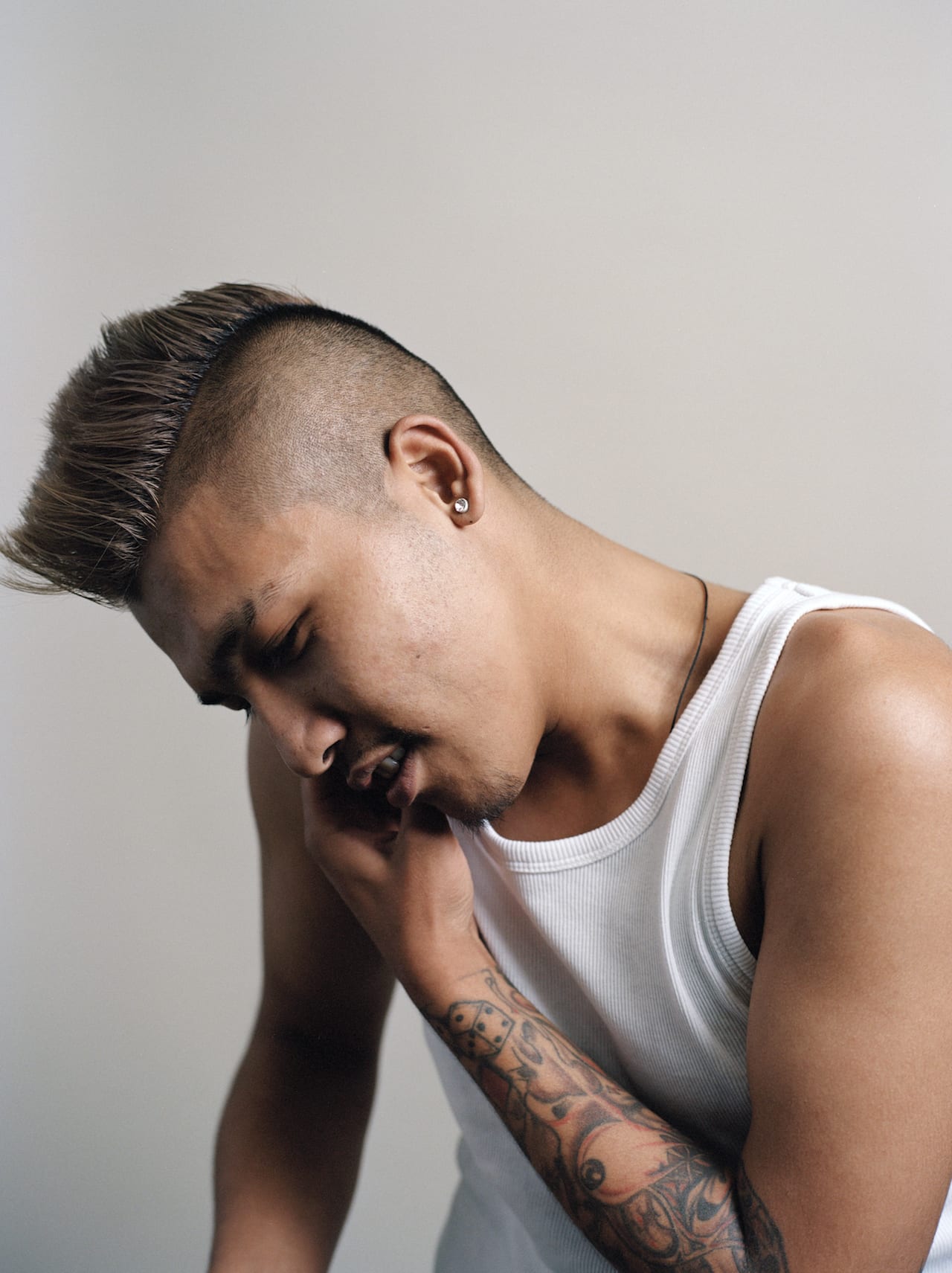

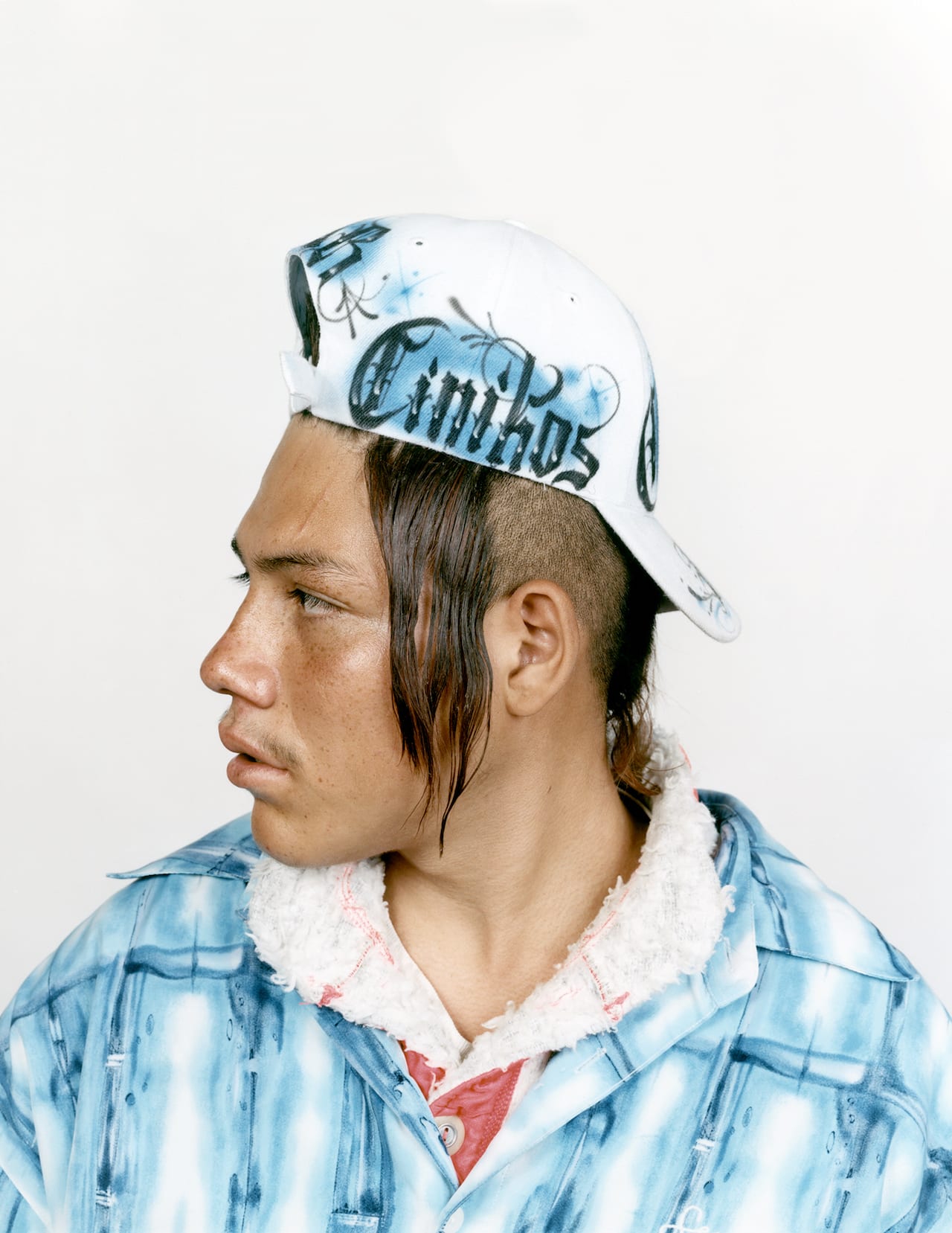

“I like objects that don’t have much of a style. Like patterns in colouring books, clean black lines, and primary colours. Things that aren’t trying to sell you an ideology or concept,” says Peng Ke, who calls from her home in Shanghai, where she has just closed her first solo exhibition in the city, I Have Seen Many People Although They Have Not Seen Me. “Most visual languages are so coded, so if I see things that are almost innocent, they really stand out to me.”

Peng Ke’s exhibition coincided with the launch of Salt Ponds, her first book published by Jiazazhi. The project has been ongoing for five years now, but only became a solid body of work after her friend and graphic designer Pianpian He approached her to collaborate on a book. It began in the cities where Peng’s parents grew up, and quickly expanded to other fast developing, smaller cities in China. Though they are shot hundreds of miles apart, her photographs are anonymous; you can never tell which city she is in. So the project became less about her own hometown, and more about the collective experience of Chinese people who live in these places, “because in a way, everyone comes from the same city”.