In the first instalment of a new series, we reflect on projects made inside, including work by Gideon Mendel, Jerome Ming and Stefanie Moshammer

In the first instalment of a new series, we reflect on projects made inside, including work by Gideon Mendel, Jerome Ming and Stefanie Moshammer

Louise Baring’s scholarly book on child prodigy Jacques Henri Lartigue locates his photographs within the extraordinary era that they were made

At breakfast, Anastasia Samoylova often eats in the company of photo books — engaging with familiar works anew, and paying homage to their makers

“I am drawn to the details and the things that you would often pass by,” says the photographer, whose surreal still lifes monumentalise the materials of knife-maker Stuart Mitchell’s trade

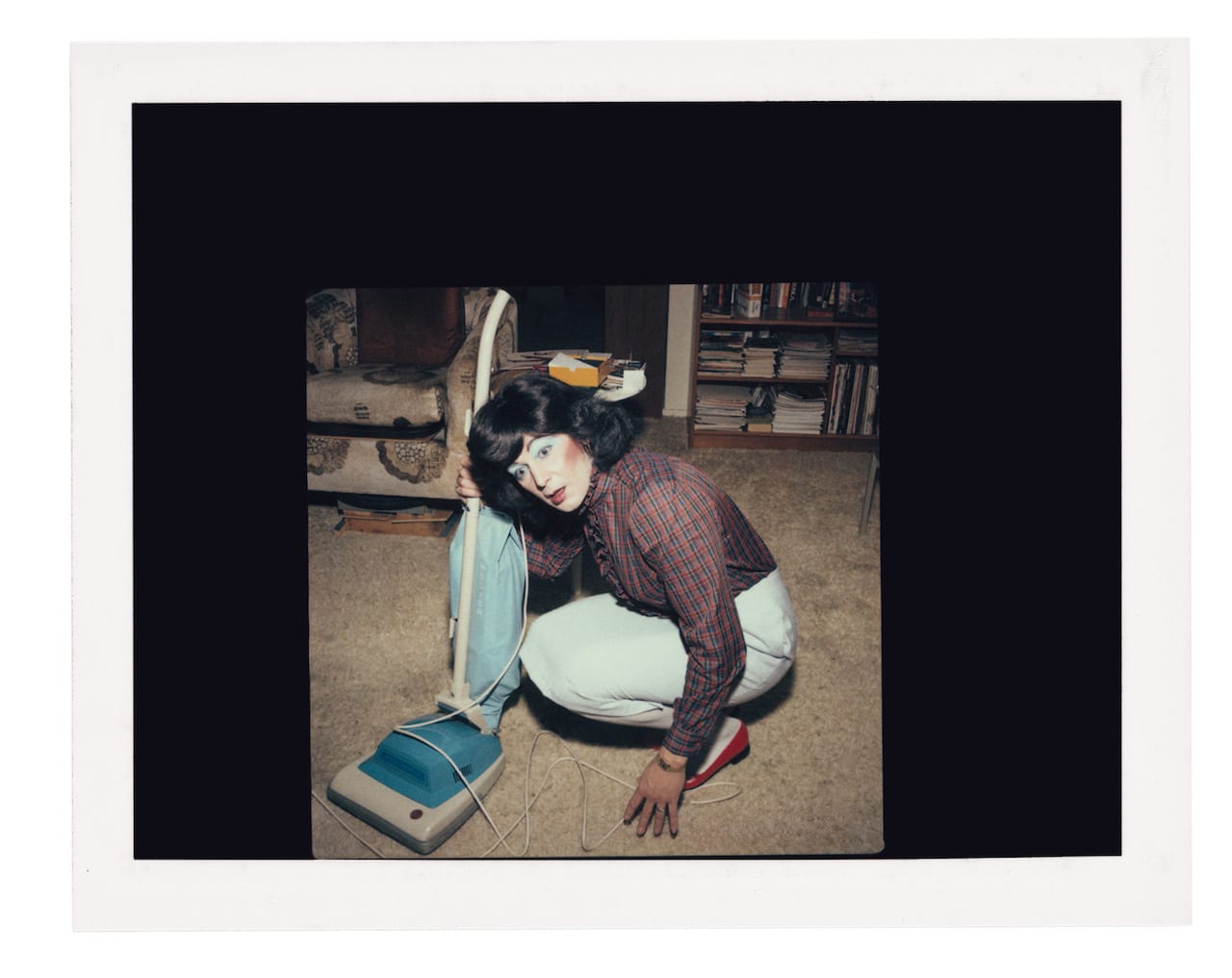

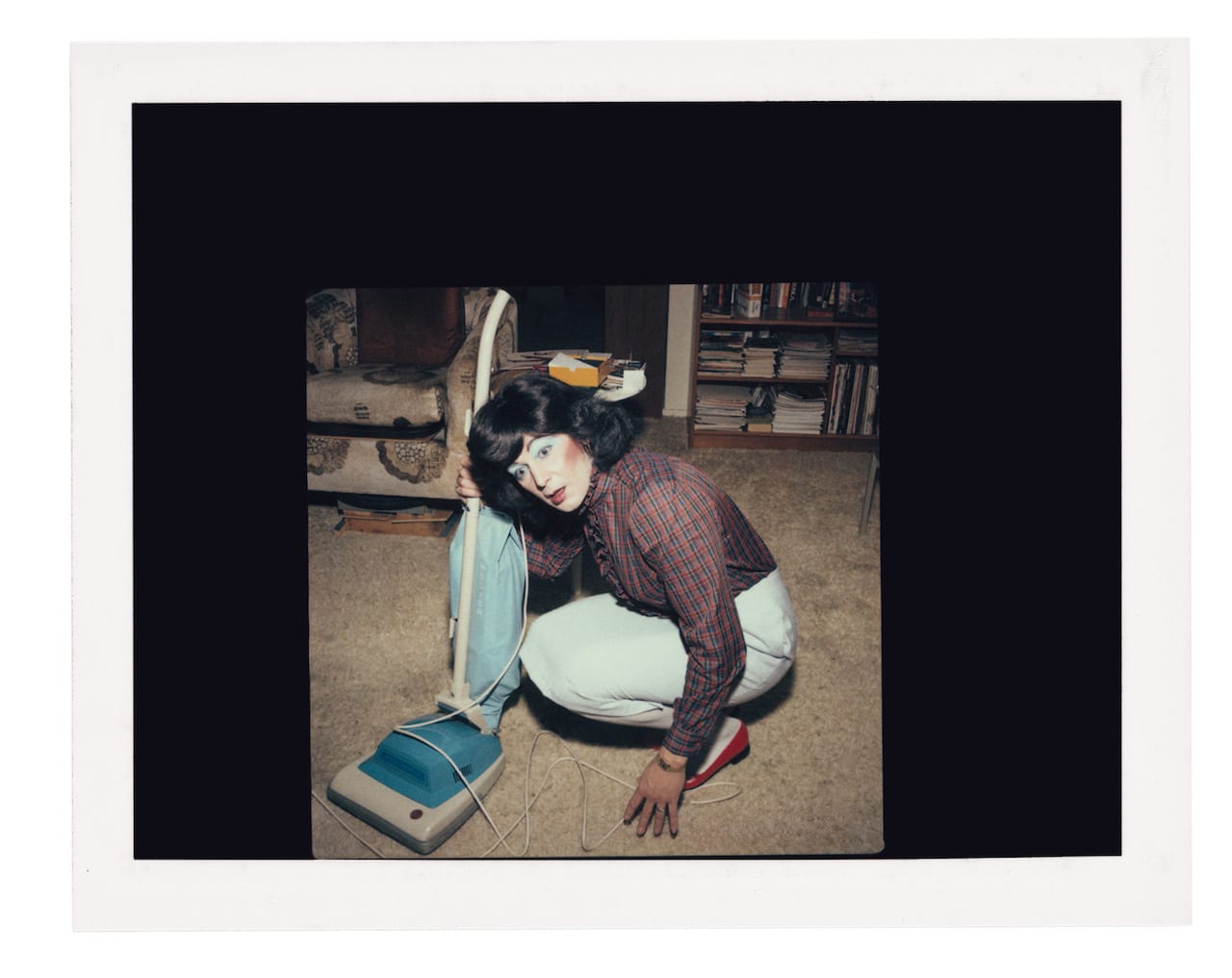

Two years after the donation of Groover’s entire archive, a major retrospective at Switzerland’s Musée de l’Elysée reflects on her influence and creative process

The German photographer’s diaristic images of friends and found objects go on show in Los Angeles

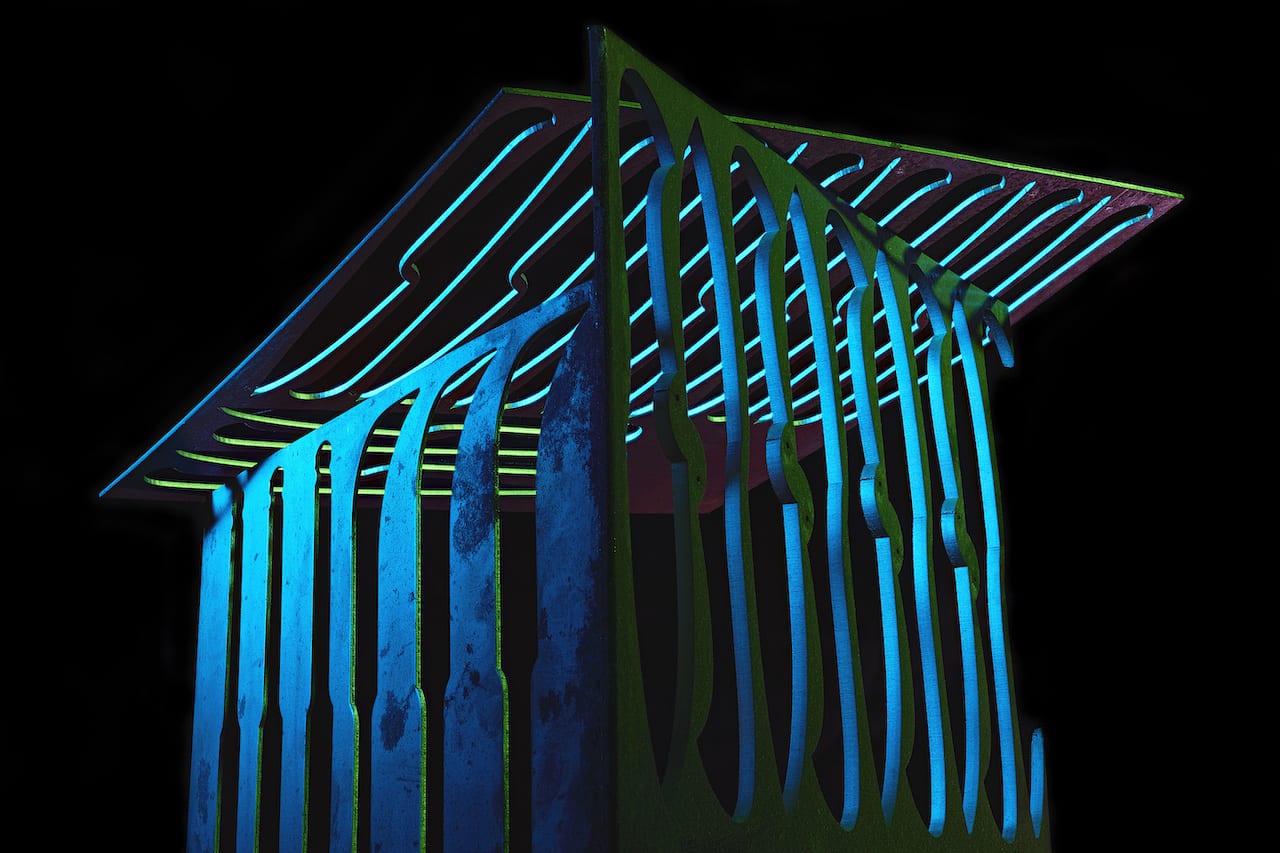

Maurice Scheltens and Liesbeth Abbenes have long been preoccupied by perspective. In fact, this year is the 18th that the artist duo – partners in life, as well as in work – have spent creating their painstakingly controlled scenes to capture on camera together. Translating their immaculately constructed three-dimensional sets into technically precise two-dimensional images, they have made a name for themselves with rich, playful and illusory works that toy with spatial dimensions, and which, though aesthetically pleasing, are conceptually rigorous first and foremost. The concept, Abbenes assures us, always precedes the picture.

Their spring exhibition at Amsterdam’s Foam Museum (from 15 March to 05 June) is something like a retrospective, giving the Dutch duo an opportunity to look back over almost two decades of work from a new perspective. And true to form, they are first rearranging the rooms their work will inhabit by uncovering windows that have not been opened in many years. “We will have light and some fresh air, hopefully. We have to give up walls for that, but it’s good to have a bit of the outside world coming in,” they say. Shifting the dimensions and conditions of the space itself will alter the way viewers see the work, and that typifies their approach to the exhibition, rethinking how the works will appear in this new context, and how they relate to each other.

What happens when you put a white flower in a vase of coloured water? It’s an experiment some of us might fondly remember from our childhood, magically transforming a bunch of flowers with a dash of food colouring.

But the results are a little more frightening in a similar experiment by French artist Cornelius de Bill Baboul, as his flowers suck the colour out of sugary energy drinks. “I think they look a little bit like dancers,” he says. “Like kids on ecstasy in a techno club celebrating the end of the world”.

“Your memory isn’t like a file in your hard-drive that stays the same every time you revisit it. It actively changes,” says John Houck, whose images, just like our memories, can be deceptive. His pieces are made cyclically, by photographing and rephotographing objects, paintings, and sheets of folded paper, adding and removing elements with each iteration. “It’s a way to get at the way in which memory is an imaginative act,” he says.

There is something frantic about David Brandon Geeting’s photography. In his latest collection, Amusement Park, the Greenpoint, Brooklyn-based artist creates a mood that is exhilarating and vibrant, but also verging on collapse, as though its tether could snap at any moment. Where his 2015 book, Infinite Power, was energetic and kinetic, with Amusement Park he’s aiming for “information overload”. “I’m not afraid of making people confused or dizzy,” he says. “I wanted it to be an onslaught of colours and forms and things that don’t make sense.”