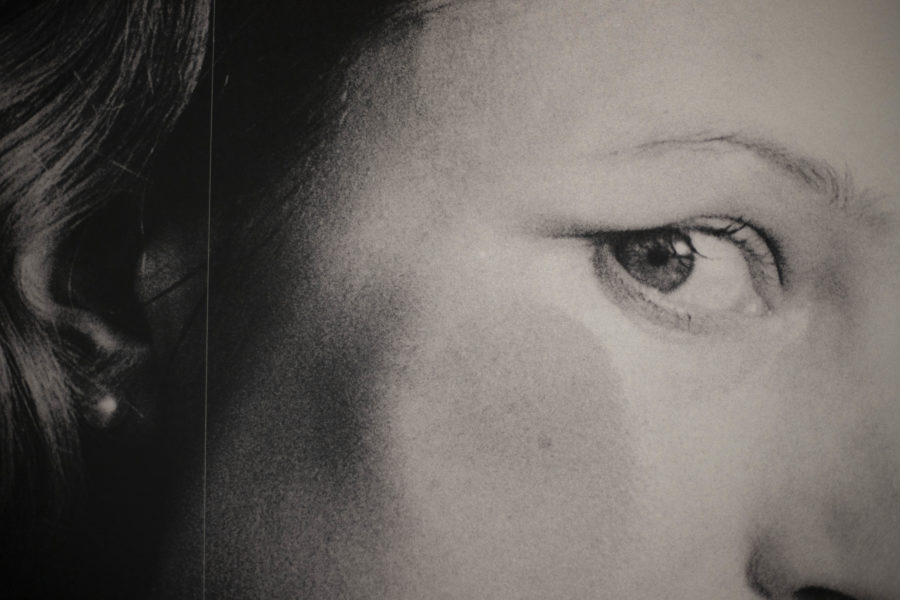

The One to Watch discusses her early influences, perceptions of the nude, and her transition from graphic designer to image-maker

The One to Watch discusses her early influences, perceptions of the nude, and her transition from graphic designer to image-maker

Established in 2013, Kyotographie is now one of the biggest photofestivals in Asia. This spring it returns for its 12th edition with exhibitions themed around ‘Source’

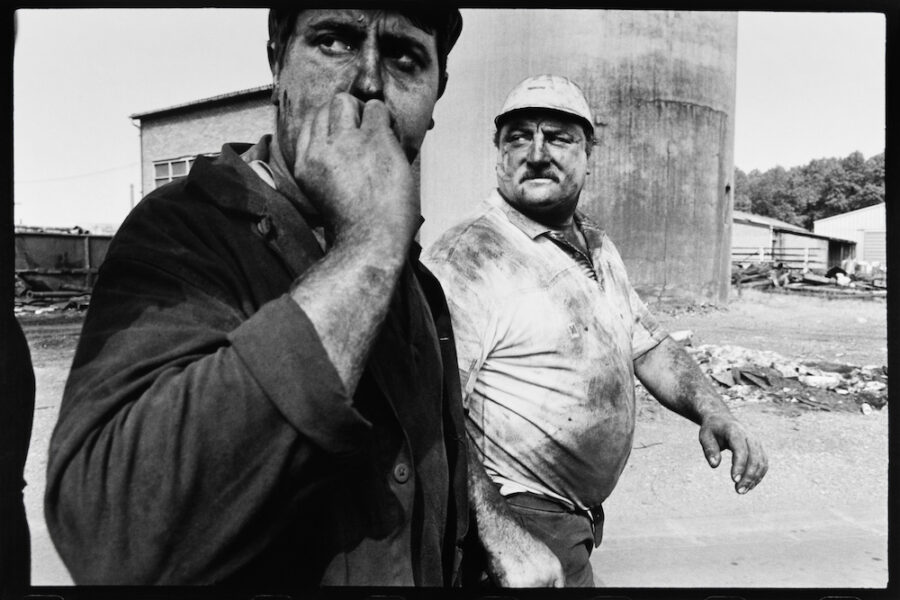

Based in a former mining area in northern France, Centre régional de la photographie is honouring the past to bring photography to the present. Director Audrey Hoareau reveals the innovative ways the centre is reaching out to the local community and beyond

Set in the village of Prabert in France, Rousset’s images play on the eccentricities of the village and its people, transforming them lovingly into caricatures and tableaus

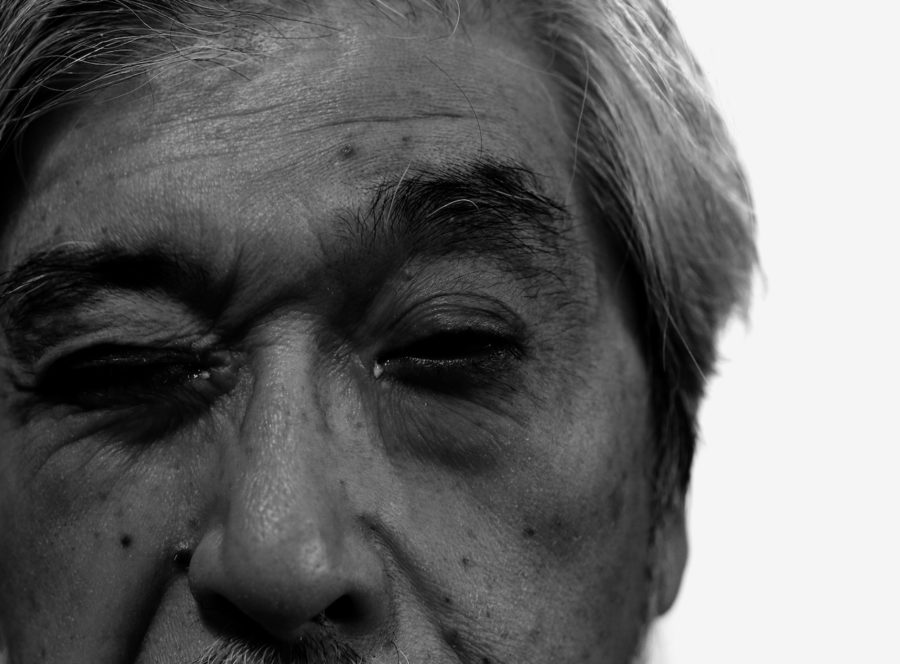

Suzuki’s latest book is titled Sokohi: a Japanese word used to describe visual impairment that translates as ‘shadow at the bottom’

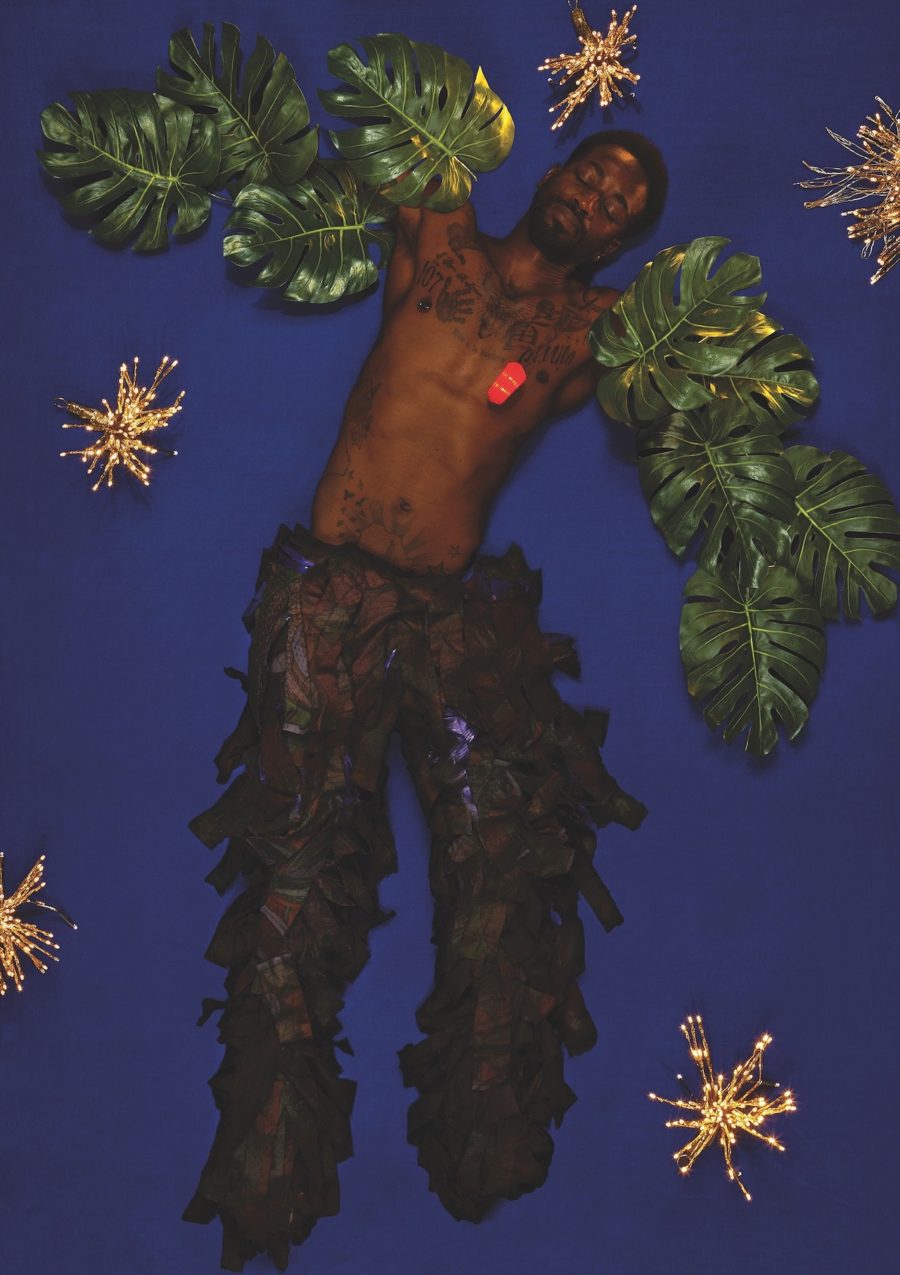

Born and raised in Paris by immigrant parents, French-Algerian photographer Maya-Inès Touam describes her work as being “between the two shores of the Mediterranean”

In the first of a series of articles looking back at some of the most exciting shows at Les Rencontres de la Photographie, Holly Roussell recalls her curatorial experience at La Croisière