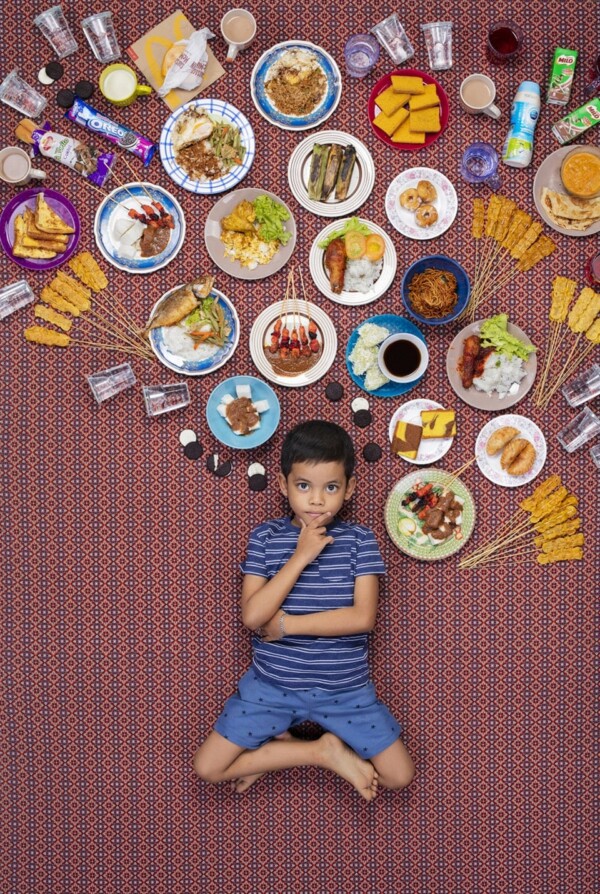

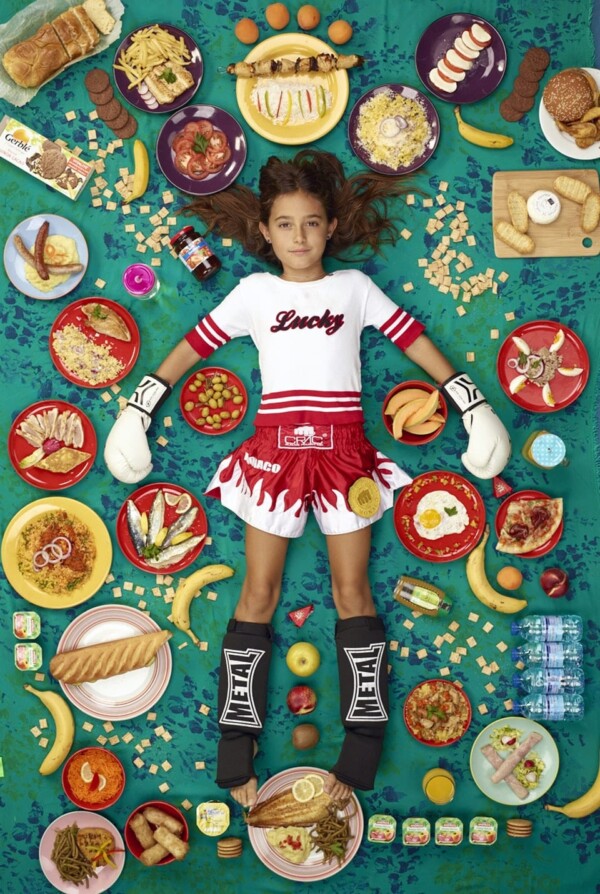

In an 8×8 aluminum hut on a construction site outside Mumbai, Anchal Sahni sits down to dinner with her family: homemade aloo bhindo (okra and potatoes simmered in curry) and chapati (flatbread) with a side of lentils. Anchal has a healthier diet than many middle-class kids in India, who can afford to eat out. In Mumbai, a medium Dominoes pizza runs 13 bucks — about three times what Anchal’s father earns a day. Sensing a sea change in Western attitudes toward diet and the effects of junk food, fast food companies have begun investing heavily in foreign markets where public awareness isn’t as keen — and where Big Macs aren’t junk, but a status symbol. In 2015, Cambridge University conducted an exhaustive study, identifying countries with the healthiest diets in the world. Nine of the top ten countries are in Africa, where vegetables, fruit, nuts, legumes and grains are staples and where meals are homemade; this is a stark contrast to the US, where nearly 60% of the calories we consume come from ultraprocessed foods, and only 1% come from vegetables. As globalization alters our relationship to food, I’m making my way around the world, asking kids to keep a journal of everything they eat in a week. Once the week is up, I make a portrait of the child with the food arranged around them. I’m focusing on kids because eating habits – which form when we’re young – last a lifetime, and often pave the way to chronic health problems like diabetes, heart disease and colon cancer.