Last autumn, Odesa Photo Days Festival ran the Photographic Storytelling Mentoring Programme, empowering young artists to document how the war has affected their lives. The 40 projects tell stories of trauma, displacement, resilience and hope

Volodymyr Mateichuk, 19, Kolomyia

Kolomyia is a small city in western Ukraine with a population of around 60,000. My project, Reliable Home Front, shows the life of a home front city during a full-scale war with Russia. Constant air raid alerts and military funerals are intertwined with people’s daily lives. People are used to monitoring the news all the time. I took these photos in the eighth month of the war. The volunteer centres, which were overcrowded at the beginning of the conflict, were half-empty.

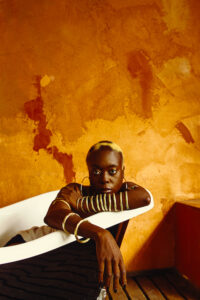

Krystyna Novykova, 20, Mariupol and Milan (Italy)

Before the war, I studied acting and directing in Kyiv. I am now working on a play in Milan. Cinema, theatre and photography coexist for me. I try to find balance between not limiting myself to only one thing and being focused and precise in what I do here and now. Sometimes I succeed.

The invasion changed time, space and the very form of existence for me forever. I’ve been in a phantasmagorical dream, where present and past intertwine. My feelings, body and memory are deformed. There’s a permanent state of tightness and suffocation. Printed photos are my only physical connection with Mariupol – my first love – now. They seem to be sewn into the skin. But my memory of the city is not distorted. On the contrary, it becomes even more clear and detailed every day. This project is an attempt to recreate the new reality, which perhaps I will never be able to get used to.

Tim Melnikov, 19, Odesa

Since the first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I’ve been staying in Odesa and documenting city life in my project Odesa: Living with War. I wanted to show how the desire to live breaks through the realities of the bloody war, frequent shelling and depressive uncertainty.

For eight months of the war, Odesa has changed dramatically and acquired the features inherent to a front line city, although it is located 150 kilometres from the front line. In the summer, the city saw no tourist season because of mined beaches. Many civilian institutions, hospitals, schools and universities were provided with protective structures in case of shelling.

Despite all of this, Odesa is alive, although it is not as vibrant as it was. Wartime Odesa is deserted and gloomy, but not broken.

Kateryna Boklan, 19, Kyiv and Plzeň, Czech Republic

I’m interested in analogue film photography. My objective is to implement a project that would make a difference in society. I took these pictures in Berlin in 2022. Through my photos, I try to remember things that really matter, about feelings, and about ourselves.

Should We Look Up to Adults? Hello, adults. There is a question: should we really look up to you? You ignored the mistakes of your ancestors. Well, this became our death sentence. We couldn’t bring our dreams to life. We didn’t have time to discover the world, but if we had… Do you think there would still be chaos? Would we steal, lie, destroy and kill in the future as you do now? Did we get you right? Sincerely yours, because we can’t be otherwise, children.

Ivan Samoilov, 20, Kharkiv

I’ve spent my whole life in Kharkiv and I’m staying here now. I study at the Kharkiv State Academy of Culture and want to become a cinematographer. I’ve been interested in photography for five years now, and started shooting regularly two years ago. I’m interested in both documentary photography and video documentaries. I like to walk around the city, take pictures and create! I see my future in my hometown, in a peaceful Ukraine.

Last summer, I got to go to North Saltivka for the first time, which is now the most war-stricken district in Kharkiv. I had never before seen such devastation. Only rescuers, old people, volunteers and homeless animals maintain some kind of life in the ruined, nearly destroyed city.

The central streets of Kharkiv are still recognisable, but a lot has changed: most establishments are closed or have been destroyed together with the buildings they were located in. Cultural life has descended to bomb shelters. You can attend poetry nights in a basement, chat with a few friends who have stayed in the city, but then a siren goes off and you have to look for the entrance to the nearest metro station in complete darkness.

Anna Pohorielova, 19, Kharkiv and Winterthur (Switzerland)

I’m a third-year student at the Kharkiv State Academy of Culture. I took up fine art photography in 2021. I combine vernacular photography and documentary photos from Kharkiv, which I took in September 2022 during a temporary return to the city. In addition to self-portraits, the photos from the family album include my parents, grandparents, and sisters. The photo of a girl with a cloth on her head was taken two days before the start of the war. Later, Valeria, the heroine of this photo, became a volunteer and died.

I’ve fled Ukraine because of the invasion. I’m now living abroad. Six months ago, I felt too much at once, and it seemed I was too exhausted to focus and create. Odesa Photo Days saved me. For now, I’ve decided to focus on street photography. This is how I prefer to feel the world: rhythm, colours, voices and music.

Vladyslav Safronov, 19, Kyiv

I studied sociology, but left the university after the war started. I’m now at the Ukrainian Film School, studying to become a camera operator. I’ve been into photography since 2019, and in May 2022 became interested in fine-art photography. I try to apply a cinematographic approach to my shots.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has changed the lives of thousands of Ukrainians. I’m no exception. These events have forced me to rethink my attitude to the world, and I’ve decided to convey every stage I’ve gone through.

Kamila Karpenko, 17, Nizhyn

In my spare time, I perform on stage and play Mafia with friends. I like reading too. Remarque is my favourite author. I’m fascinated with his work. I feel related to some of his characters and their feelings. He wrote that “There are stars that disintegrated 10,000 light years ago, but they still shine today.”

The Germans killed 6700 residents of the town of Koryukivka at the beginning of March 1943. A little girl and her family survived, but she still can’t forget this terrible episode of her life. Halyna Popova is an eyewitness of those events; she recalls the impudence of the military, people’s fear, confusion and panic, many bodies on the roads and the difficult path to freedom.

Her mother saved the family by bringing children outside the fence, but there were many people left who didn’t make it. The whole town was on fire and ruined. It became lifeless. The time passed and people started returning and rebuilding their homes.

People now walk along the streets as they used to do in the past. Have they forgiven that cruelty? Will they be able to forgive later on? Most Ukrainians who are connected with the occupiers – whether through the territories, family ties, or the time they lived together – should also answer this question.

My pictures were taken in Nizhyn and Koryukivka in 2022. I’m trying to address forgiveness: how long can a person keep pondering an issue in order to let it go and make life easier? Will such a decision make it easier – or is it better to continue to think it over?

Mykyta Bezus, 19, Kamianske and Kyiv

I study at the Faculty of law at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Originally from Kamianske, I live in Kyiv, though I’m originally from Kamianske.

In our situation, it is difficult to predict how the next day will pass, let alone the next week. When we give up and refuse to live on, we make a priceless gift to those who expect this from us. Being strong and resistant means to thwart all enemy’s plans to destroy our life.

My series Dawn is about Ukrainian young people, their places of strength, important things and life after 24 February.

Marharyta Rubanenko, 21, Popasna and Toruń (Poland)

I am a photographer, art manager and student. I was born in Popasna, Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine. In recent years, I have lived, studied and worked in Kharkiv. I was forced to move to Poland because of the war.

At the end of April, I received a photo from my neighbours’ friends, showing that the house where I had spent my childhood didn’t exist any more. A bunch of keys is all that is left.

I have no access to a rented flat in Kharkiv either. It’s still too dangerous to stay in the city because of shelling; people die every day there. Despite this, in the first months after moving to Poland, I couldn’t allow myself to take the keys to that flat out of my pocket. I always took them with me.

When the war forces you to leave your home to stay safe, taking your keys means a hope to return home as soon as possible. Unfortunately, now it becomes clear that many people will have nowhere to return to, because their homes are destroyed, or if otherwise, it’ll take a lot of time, until it’s safe to come back.

For my project, House Keys, I’ve collected the stories of people who can’t return home due to various reasons. They continue living with this, even smiling, despite what they have gone through, and carrying keys to their home. They want to come back one day.

Find out more about Odesa Photo Days Festival here